As is usually the case when I prepare my pre-concert lectures at the Chicago Symphony, I end up with way more information than I can share in the 30 minutes allotted. Here are some extra insights on the Dec. 10 – 12 concert series, featuring the “Metamorphosen” of Richard Strauss. Welcome CSO patrons!

Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings (1945)

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

During the war years, the German composer Richard Strauss found himself increasingly disillusioned with the world and with himself. He had once been the daring enfant terrible of the musical world, then an upholder of its traditions, finally an elder statesman of German culture. All this came crashing down around him during the Nazi era.

Frankfurt after Allied bombing, home of the Goethe House, which Strauss described as “the most sacred place on earth.”

It is worth exploring in further detail Strauss’s relationship to the Nazi regime. It is true that in 1933, he was named President of the Reichsmusikkammer (Music Bureau) and that in this position he did befriend some high ranking Nazi officials. However, he eventually would use these contacts to save his Jewish daughter-in-law and his half-Jewish grandchildren.

In any case, he never joined the Nazi party and his work always came first in his life: he refused to disavow his collaboration with the Jewish librettist Stefan Zweig and was thus removed from his government post.

from Die Liebe der Danae

Strauss’s mood was poignantly conveyed by an episode in August 1944. His new opera, Die Liebe der Danae was set to premiere at that summer’s Salzburg Festival, but shortly before the opening, all German theaters were closed due to the attempted assassination of Hitler and the declaration of Total War. Strauss was torn with grief, and felt that he would never have a chance to hear his work.

A single open dress rehearsal was negotiated so that Strauss would in fact be allowed to behold his creation. The composer was deeply moved by what he heard and saw, and apparently during the orchestral interlude before the final scene (playing above), he wandered down the aisle to the orchestra pit and exited the hall in a daze. How could anyone not be moved by music of such transcendent beauty:

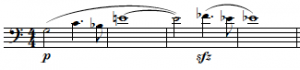

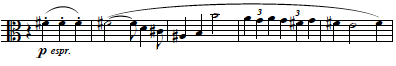

Strauss’s beautiful orchestral piece Metamorphosen is perhaps our only true insight into his spiritual view of the brutal Nazi regime and its weathering of his soul. However, it is also a display of Strauss’s technical mastery of several themes. The piece opens with a particularly dark theme presented in the celli and basses:

Metamorphosen: first theme

https://www.willcwhite.com/audio/danae.mp3

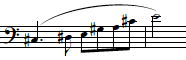

if you listen carefully, you may also hear the principal counter-theme in the lower cello part:

principal counter-theme

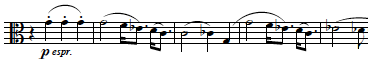

However, Strauss’s main interest in this piece lay not with the first theme that we hear, but with the theme that directly follows it. This principal theme bears a distinct similarity to the Funeral March from the second movement of Beethoven’s 3rd Symphony. It is possible that Strauss meant for this theme to represent the entire history of German musical culture.

Metamorphosen: principal theme

Beethoven Symphony No. 3: funeral theme

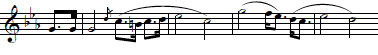

This theme undergoes a sort of “metamorphosis” and becomes the third main theme of the piece:

Metamorphosen: 3rd theme

https://www.willcwhite.com/audio/danae.mp3

These themes combine into highly climactic music of raw emotional power:

https://www.willcwhite.com/audio/danae.mp3

and the piece finally concludes with Strauss’s actually quoting Beethoven’s symphony:

https://www.willcwhite.com/audio/danae.mp3

Finally, a mathematical thought: I think it is very likely that Strauss was playing a sort of numbers game in his conception of this piece. Note that it is written for 23 solo strings: a prime number. It is built up of additional primes: 5 first violins, 5 second violins, 5 violas, 5 celli, and 3 basses.

Interestingly, certain conductors — namely Herbert von Karajan, whose recording graces this page — have seen fit to augment the string numbers with additional players. Karajan did this only in the loudest sections, but it still seems to me rather unnecessary, given the fact that Strauss so carefully worked the architecture of the piece to take advantage of every possible combination of the 23 players.

For more information on Strauss, I highly recommend Michael Kennedy’s Richard Strauss: Man, Musician, Enigma, a thoroughly enjoyable read available at amazon.com.

Feel free to leave a note in the comments section to share your opinions of the concert! Also, feel free to peruse the rest of my site at your own risk, in full awareness that hereafter, the Chicago Symphony/Civic Orchestras have nothing to do with the content on this site…