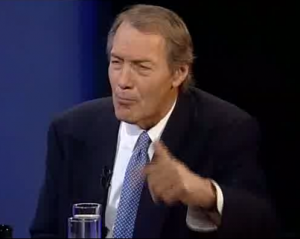

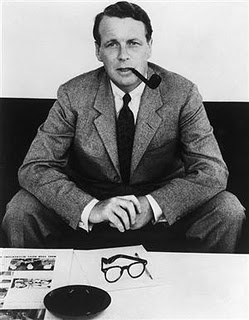

Charlie Rose plays an inordinately large role in my life*. He is quasi avuncular – sometimes a chum, sometimes a father-confessor. In the space of a single interview – a single question, really – he can be simultaneously awkward and brilliant, bored and engaged. To gaze upon him is to know that he is a man of intense contrasts: how can one man look so boyishly handsome and so ruthlessly haggard at the same time?

*[in my head]

Charlie is my particular subject today because he’s been giving a lot of love to the classical music world lately, but we’ll get to that in just a second. I want to pause here to state publicly that even though I will fight valiantly to make sure cuff links remain a vital part of the male wardrobe, I love that Charlie just doesn’t wear them. In fact, sometimes he won’t even bother to button his ordinary cuffs:

And in that picture, he was in London for goodness’ sake! Ok though, enough about Charlie’s clothes. [And trust me, I could go on.] Charlie has always been a great friend to the classical music community, but there’s been a recent spate of interviews that I’d like to talk about. Let’s begin with the most interesting:

Valery Gergiev, in his 2nd or 3rd appearance on Rose, gave a blisteringly efficient and wide-ranging interview. This was the Charlie Rose broadcast at it’s best: engaging, insightful, convivial, mutually respectful. Plus, if anybody has ever embodied the phrase “rakishly handsome”, it would Valery Gergiev – which is astonishing in a world where we have Charlie Rose! [see above] Let’s just say, this was a meeting of equals.

Bar none, the most interesting part of this interview was the last five minutes, in which Charlie posed Gergiev one of the most surprising questions I’ve ever heard him ask: Who are the 5 (or 6) most important living composers in your eyes?

The reason for my surprise is that there are so few people in this world who are in any way interested living composers (the concert/art/academic kind, that is). Charlie Rose could not possibly have expected to recognize any of the names on Gergiev’s list (unless happened to fall under the elusive “unknown known” category), and yet he asked the question. I have never loved him more.

Let’s take a look and listen to Gergiev’s list of composers, shall we?

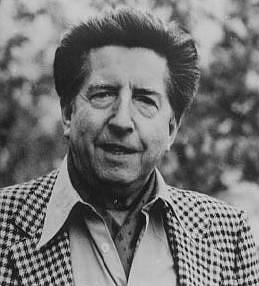

Rodion Shchedrin

Shchedrin is an interesting choice, I’d say. Most Westerners, if they’ve ever heard of this composer at all, have only heard of one piece: the “Carmen Suite”, a sort of cartoonish, barbaric Russian ballet-fantasia on themes from Bizet’s Opera:

Shchedrin is an interesting choice, I’d say. Most Westerners, if they’ve ever heard of this composer at all, have only heard of one piece: the “Carmen Suite”, a sort of cartoonish, barbaric Russian ballet-fantasia on themes from Bizet’s Opera:

Shchedrin is often compared to Schnittke, and it’s not an unwarranted (though don’t get me wrong, I know Alfred Schnittke, and Rodion Shchedrin is no Alfred Schnittke). At his poppier moments, Shchedrin sort of comes off as Schnittke-meets-John-Williams. Gergiev makes a compelling case for the composer on his new album:

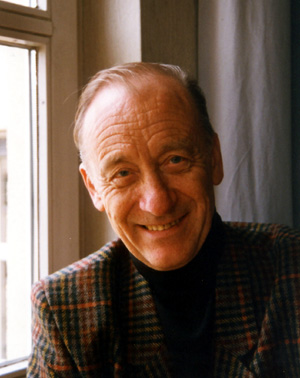

Henri Dutilleux

Dutilleux came as a surprise a) because I honestly did not know that he was still alive, and b) it’s not that he’s necessarily a bad composer, but I’ve never known anyone to be a major fan or champion of his music, and I certainly had no inkling that Gergiev might be that person (say in the way that Kent Nagano and Olivier Messiaen are associated w/ each other).

Dutilleux came as a surprise a) because I honestly did not know that he was still alive, and b) it’s not that he’s necessarily a bad composer, but I’ve never known anyone to be a major fan or champion of his music, and I certainly had no inkling that Gergiev might be that person (say in the way that Kent Nagano and Olivier Messiaen are associated w/ each other).

I’ve always thought of Dutilleux as a sort of solid but not terribly interesting mid-2oth century modernist. I don’t know much [his] of music, so perhaps that’s not fair. Give a listen and see what you think – this is the opening movement of his “Metaboles” and is the piece I’m most familiar with by him:

Raskatov is Gergiev’s near exact contemporary (they were born like 2 months apart). Raskatov has actually figured prominently on this blog before. Allow me to job your memory: he is the very person who painstakingly reconstructed Alfred Schnittke’s 9th Symphony. This was no easy job, and by all accounts, he did very, very thorough work. I mean, the piece that we can hear today sounds like Schnittke, and it’s all because of him. Respect.

Raskatov is Gergiev’s near exact contemporary (they were born like 2 months apart). Raskatov has actually figured prominently on this blog before. Allow me to job your memory: he is the very person who painstakingly reconstructed Alfred Schnittke’s 9th Symphony. This was no easy job, and by all accounts, he did very, very thorough work. I mean, the piece that we can hear today sounds like Schnittke, and it’s all because of him. Respect.

The Schnittke symphony was released on CD and that’s how Raskatov first came to my attention. You see, he included a new piece, a Nunc Dimittis in Memoriam Alfred Schnittke (or Alfredom Schnittkom, I think, if we’re being correct about our Russian grammar.) And it’s like, honestly, can you hardly blame the guy if he wants to put his own piece on this album after doing all that work? I can’t – I’m sure I would have done the same thing. And it’s not that it’s a bad piece. It’s very Schnittkey, but you know, it’s just not going to come off so amazing in comparison when you pit it against this amazing transcendent work by an artist who was already halfway to the grave. Here’s maybe my favorite section:

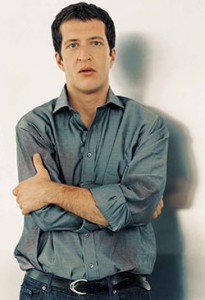

Thomas Adès

With all due respect to Gergiev’s Ruskii compatriots, I would have started my list with Thomas Adès. Adès is arguably the most important, greatest, most tubular -whatever adjective you want to use- composer of concert music we have around these days. And it’s not a hard argument to make. Whether we all choose to realize or admit it, we composers today are living in the shadow of Ligeti. (In Russia, Schnittke is the looming presence. Give it time, and he will creep westward.)

With all due respect to Gergiev’s Ruskii compatriots, I would have started my list with Thomas Adès. Adès is arguably the most important, greatest, most tubular -whatever adjective you want to use- composer of concert music we have around these days. And it’s not a hard argument to make. Whether we all choose to realize or admit it, we composers today are living in the shadow of Ligeti. (In Russia, Schnittke is the looming presence. Give it time, and he will creep westward.)

Despite this pervasiveness, Adès is really the only major figure who is seriously grappling with the specter of Ligeti. And he’s none the worse for wear. Here is the first movement of Ligeti’s Violin Concerto, about a minute in:

and here is the opening of Thomas Adès’:

It’s not that the two pieces sound all that similar – my point is that they seem to inhabit a similar universe but they are worlds unto themselves. The act of homage is subtle: both composers build rhythmically complex textures that are nonetheless extremely quiet; the effect is a luminescent haze of sound.

I think it’s significant that not only that Adès handles himself adeptly in a dialogue with Ligeti but that he’s chosen late Ligeti as his conversant [I might mention that Adès’ concerto also shares aspects with Ligeti’s Hamburg Concerto.] Again, he’s not an imitator or a provocateur or anything like that – he’s got a very strong singular talent, perhaps one of the few strong enough to really grapple with Ligeti’s writing.

As for Charlie’s interviews with Vittorio Grigolo and Antonio Pappano, I’ll just point out a few things:

1) Grigolo might be the most Italian Italian person I’ve ever heard. No offense to my Italian friends, but they tend to say in about 100 words what they could manage in 10.

2) You just know that right before the cameras started rolling, Charlie made Vittorio coach him on the correct Italian pronunciation of his name. Charlie really tried to retain this knowledge as he introduced his guest, and though this was definitely his most valiant effort yet at a foreign pronunciation, it still comes out gloriously mangled.

2) Plus, if you skip ahead to 16:42, you’ll see that Vittorio loves Charlie, and so do I.

3) Watch Antonio Pappano at the beginning of the show as Charlie is introducing him. Do you see him subtly lip syncing the whole speech? That’s kind of really weird, right?

I rambled into the message box and cleaned things up later, but I never had any doubt about sending so much detailed, practical information, because I know that that’s what people like best. Read David Ogilvy’s

I rambled into the message box and cleaned things up later, but I never had any doubt about sending so much detailed, practical information, because I know that that’s what people like best. Read David Ogilvy’s  I love specific, detailed, technical information, and that element might be my most favorite thing about

I love specific, detailed, technical information, and that element might be my most favorite thing about  And then there’s my friend André’s new web site,

And then there’s my friend André’s new web site,