I wrote this song for my friend Leann Schuering. We went to college together and – OK, just go read her blog, she already explained this whole thing!!

Just to Sing from Leann Schuering on Vimeo.

Musician

I wrote this song for my friend Leann Schuering. We went to college together and – OK, just go read her blog, she already explained this whole thing!!

Just to Sing from Leann Schuering on Vimeo.

Osvaldo Golijov (1960 – )

Osvaldo Golijov (1960 – )

Sidereus

Osvaldo Golijov is the composer of such blockbuster classical hits as The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind and the toe-tapping Pasión según San Marco:

Mr. Golijov’s pieces often have more the flavor of an ethnomusicological exploration, which makes a certain amount of sense for a composer of Argentinian birth who grew up on klezmer and tango and who has also lived in Israel and the U.S. [Although, is it really ethnomusicological if it’s actually your ethnicity? Discuss.]

Anyone who attended Thursday’s lecture was privy to insights from the work’s dedicatee, Mr. Henry Fogel. Boosey & Hawkes has provided an equally enlightening interview with the composer about the genesis of the work. You can listen to the work online in a performance conducted by Mei-Ann Chen (who gave the première in October 2010 in Memphis) with the New England Conservatory Philharmonia. Also of note is Mr. Golijov’s growing filmography since becoming the go-to composer of Francis Ford Coppola.

Lest there be any confusion, the title of Mr. Golijov’s latest work, Sidereus, is in no way meant to sound like an hilarious mispronunciation of the next composer on the program.

Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957)

Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 (1903, rev. 1905)

Sibelius’ violin concerto is far and above my favorite work in the genre, and one of my favorite works by the composer. In fact, it’s one of the first pieces that got me into classical music. You can view an introduction to the work here by the violinist Ida Haendel, who actually received a letter of appreciation from Sibelius after he had heard her performance of the work, and whose Wikipedia entry actually says the following:

She has the reputation of being as accomplished and brilliant a violinist as Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern; but has said that had she been more photogenic, she would have been as famous.

Ida Haendel

Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern, two violinists who Ida Haendel was not as attractive as

People sometimes said the same thing about Sibelius himself, but never to his face (see above).

But seriously folks, if you’re really into the Sibelius concerto, it’s worth your 10 bucks to invest in Leonidas Kavakos’ recording of the 1903 and 1905 versions of the work. He is still the only artist to record the 1903 version, due to the Sibelius family’s wishes, which is pretty impressive. He is also way, way hotter than Ida Haendel.

You’ll get to hear the intricate, Bach-like second cadenza that Sibelius later cut from the first movement of his concerto:

amongst many other interesting tidbits.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 – 1975)

Suite from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District

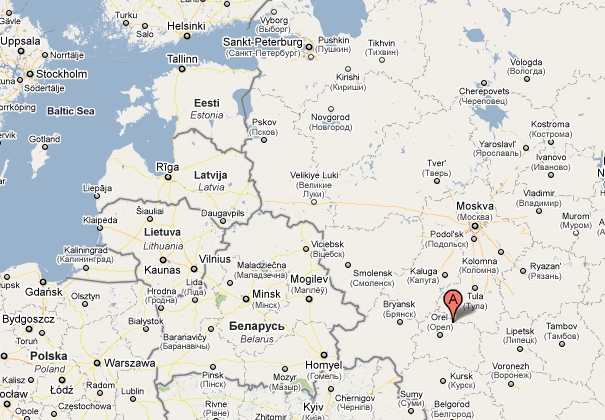

OK, first of all, if you’re anything like me, you’ve always wondered just where IS the Mtsensk District. It’s here:

The rest of this discussion I’m gonna cut and paste from my March 4, 2010 post about Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11:

Shostakovich’s troubles with the government began in the year 1936, at which point Joseph Stalin, eager to send a message to the artistic community, denounced Shostakovitch’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District as immoral and anti-soviet. Let’s watch a bit of the opera and see if we can spot anything that Stalin may have found objectionable. Remember to look very closely now:

At first glance, it looks pretty tame, but that Stalin always had a fine eye for detail. Anyhoo, that led to this very famous headline from the Soviet newspaper Pravda:

which roughly translates to “Muddle instead of Musicâ€, and which began a nightmarish 20 year period of heavy government repression and scare tactics aimed at keeping Shostakovitch in line.

I’d like to recommend two more valuable resources pertaining to Shostakovich’s music and life:

The first is the audio guide to chapter 7 of Alex Ross’s phenomenal book, The Rest is Noise. Even if you haven’t read the book or don’t have a copy handy, the audio guide gives you a nice synopsis of the chapter on music in the 1930′s and 40′s USSR.

The second is an article by everybody’s favorite Slovenian Marxist-Lacanian-psychoanalytic philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, entitled “Shostakovich in Casablanca“. In this article, Žižek compares Soviet repression of classical music to the Hollywood Hays code, in terms of what the censors expected and how an artist was meant both to abide by the code and simultaneously to circumvent it. He posits that Shostakovich found whatever success he could with the Soviet regime because he understood this Janus-faced censorship, whereas Prokofiev just couldn’t figure it out.

This concert featured pieces by four composers who were all innovators in the areas of harmony, orchestration, musical form, and music-drama. Here’s some examples of what they did and where they came from:

Carl Maria von Weber (1786 – 1826)

Below is the first part of the famous “Wolf’s Glen” scene in Der Freishchütz. Note Weber’s use of low, dark orchestral string colors and demonic shrieks from the woodwinds to represent cavorting with dark powers in this eerie space. The arrival of Max, the young gamesman, is accompanied by bright horn calls, our constant reminder that he is a man of the hunt.

[The production below, overall, is pretty cool and certainly very striking. If you are easily offended by rabbit pornography, however, I’d recommend skipping 1:40 – 1:50.]

Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869)

The best part about researching 19th century composers is getting to read their own writings. This is especially true in the case of Berlioz. Never has there been or will be a more over-the-top, extravagant musician or man, prone to bouts of depression and, especially, exaggeration. Berlioz’s Memoirs make for immensely entertaining reading, and I recommend them highly. All you have to do is look at some of the chapter and page headings:

—

—

—

—

—

Berlioz’s memoirs take us back to a time when artists still presented themselves passionately, vividly, fearlessly. In recent times, this seems to have gone out of fashion.

Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883)

The Civic Orchestra concert included the little known Wagner work Eine Faust-Ouvertüre. Another work dating from around the same period (1839 – 40) is the overture Wagner wrote for the German playwright Guido Theodor Apel’s Columbus. Here’s what it sounds like:

Wagner presented this piece on a concert that was attended by Berlioz. He writes in Mein Leben about the experience of presenting this work in Paris:

One great objection was the difficulty of finding capable musicians for the six cornets required, as the music for this instrument, so skillfully played in Germany, could hardly, if ever, be satisfactorily executed in Paris. I was compelled to reduce my six cornets to four, and only two of these could be relied upon.

As a matter of fact, the attempts made at the rehearsal to produce those very passages on which the effect of my work chiefly depended were very discouraging. Not once were the soft high notes played but they were flat or altogether wrong. In addition to this, as I was not going to be allowed to conduct the work myself, I had to rely upon a conductor who, as I was well aware, had fully convinced himself that my composition was the most utter rubbish – an opinion that seemed to be shared by the whole orchestra. Berlioz, who was present at the rehearsal, remained silent throughout. He gave me no encouragement, though he did not dissuade me. He merely said afterwards, with a weary smile, ‘that it was very difficult to get on in Paris.”

Arnold Schoenberg (1874 – 1951)

Schoenberg is so well known both by lovers and haters of 20th century modernism as its radical founding father, that it’s interesting to remember his firm grounding in the Wagnerian Romantic tradition: