Have you all heard of this thing called “The Boar’s Head Festival”, not to be confused with the deli meats? ‘Twas begun in Oxford in 1340, and apparently it’s so very English that I hadn’t come across it, but lo and behold it’s a big deal at Christ Church Cathedral in Cincinnati, and I was unwittingly roped into participating this year.

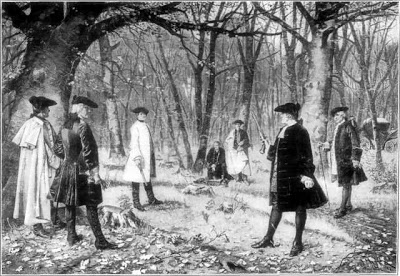

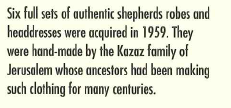

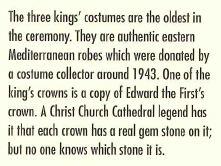

Now look. There are Christmas Pageants, and then there’s This thing. We’re talking a cast of thousands. This is Cecil DeMille meets Franco Zeffirelli meets the Renaissance Fair meets the Anglican liturgy. Here’s a description of some of the costumes directly from the program book:

and this (!)

A longtime participant in the festival told me that to get a role as a Beefeater (solder, not gin) someone literally has to die. That is how hardcore the Boar’s Head people are.

The first big number in the show is called “The Boar’s Head Carol“, sung by a saucy master-of-ceremonies type, and akin to “In Dulci Jubilo” in its mashing-up of old English and Latin texts:

Worthy of note is that this tune is basically a variation on that most lascivious ditty, Watkins Ale:

Now let’s pause and look at the first three lines of the BHC, because now we’re getting into pet peeve territory:

The boar’s head in hand bear I,

Bedecked with bays and rosemary.

And I pray you, my masters, be merrie.

I think it’s such a shame when we perform this Old- or Middle-Englishy stuff with modern pronunciation, because guys, here’s a little secret, in that last stanza, I, rosemary, and merrie are all supposed to rhyme, and in the 16th century, they did. I just finished reading The Oxford History of English, and I’ve watched this YouTube clip like 5 times, so I’m kind of an expert (see esp. 4:53):

The last comment I’ll make about the Cincinnati Boar’s Head Festival is the carols are scored for a medium-sized orchestra of strings, oboe, brass, percussion, and organ. I wish I’d had the wherewithal to record some of the orchestrations during our performances, because they are certainly interesting. All the tunes were orchestrated, for some reason, in 1962 by one Frank Levy, a cellist in the Radio City Music Hall orchestra, and all I can say is that if a cellist in the Radio City Music Hall orchestra were to have orchestrated a number of Christmas Carols in 1962, this is what they would sound like. The most interesting bits were a verse of “Kings to thy Rising” which got a bongoized 007 treatment and a particularly dark verse of “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence” which was accompanied by a hazy, Menottian cluster of strings.

Oh, and the very last thing: from this experience I learned what Waits are, and you should to.