Well, I finally did it, I finally made a recording of my children’s piece-cum-viola concerto “Cinderella Goes to Music School”, the proper title of which is really “The Viola Concerto OR Cinderella Goes to Music School” (ala G&S). I’m super proud of this project, and I hope you’ll all enjoy it greatly:

This piece was SO MUCH FUN and SO MUCH WORK at every stage of its development. It started with an idea – that I would write an original piece for my annual children’s concert at the Pierre Monteux School in Hancock, ME. But what would the piece/story be about? My inspiration came from Pedro Almodóvar: so many of this master’s films are about filmmakers making films, so why not write a piece of music about musicians making music?

The idea of transforming Cinderella into a story about a young girl violist came to me in the shower one morning in a fit of inspiration. I leapt out of the tub, threw on some clothes and scribbled down the basic plot and character outline in about 20 minutes.

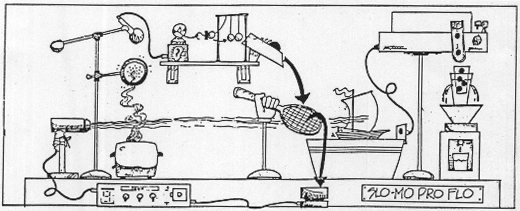

Since then, this piece has undergone many, many phases of development: after the initial composition of the script and the music, I took it to Maine, where I workshopped it with friends and colleagues last summer, and we gave the premiere. This past spring, I revised it for a different conductor/violist combo who were both involved in the original production for a performance in Cleveland. And just this past month I hired a bunch of random (and, dare I say, randomly excellent!) musicians to lay it down on the recording. Voiceover work followed (my favorite part – these are all the roles I was born to play!) and, finally, assembling the finished package with my trusted engineer Rick Andress. The final stage is heading back to the score itself – re-tooling the printed score and parts to match the many collaborative changes made over a year and a half of working.

I think the recording turned out great, and I hope that violists play it, musicians enjoy it, and most importantly, kids hear it. I dedicate it to the many “Cinderellas” both male and female I’ve known over the years – hard working violists who just don’t get the credit they deserve. The initial conception for this piece really goes back to the very hot summer of 2007, when I did little else but sit around my Chicago apartment and write beginnings to about 30 different versions of a viola concerto, all in the tief ernst, Ligeterian mode that I was into then. I’m so glad that the piece came out fun instead. Sharp-eared listeners might even hear a taste or two of Ligeti in this score.