Here’s a little Christmas gift for everybody: Peau d’Âne, the strangest film of Jacques Demy’s career, and, by coincidence, probably the strangest film ever made.

For those among my readers who are unfamiliar with the work of the French auteur, allow me to catch you up: Jacques Demy made four or five films in the late 50’s/early 60’s, but his cult following really began in 1964 when he teamed up with the legendary French jazz pianist/composer Michel Legrand on a little collaboration known as Les Parapluies de Cherbourg.

“The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” might be considered a musical, but if we’re being fussy about our nomenclature, it’s really an opera – the dialogue is entirely sung. It’s become a cult hit, and it’s absolutely worth your while to see/listen to. If you ask me nicely, I’ll come over to your house and sing the entire thing from start to finish (I will also do this if you mention it in passing.)

[A side note: my mother was 15 when “The Umbrellas” made its way over to the states, and promptly fell in love with it. She broke up with her high school boyfriend when he didn’t share her ardor for the movie. In retrospect, it probably would have been a much worse sign if her teenage boyfriend had fallen in love with a campy French musical.]

[Another side note: Stephen Sondheim’s one flaw as a human being is that he doesn’t like Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. In a sense, he’s right: it’s a ridiculous conceit with a clunky execution (the text setting is particularly disastrous.) But it’s just like, Steve, you’ve got to get past all of that. It’s ok though, I still wouldn’t break up with him.]

After “Les Parapluies”, Jacque Demy and Michel Legrand teamed up once again for “Les Demoiselles de Rochefort”, which really is a musical. Like its predecessor, it stars the incomparably ravishing Catherine Deneuve but it also features a cameos by Gene Kelly (who trots out a few mots de français) and George Chakiris.

This brings us to our special subject for today, the third and final Demy-Legrand collaboration, the incomparably strange Peau d’Âne – “Donkeyskin” – based on Charles Perrault’s incestuous fever-dream of a fairy-tale from 1695.

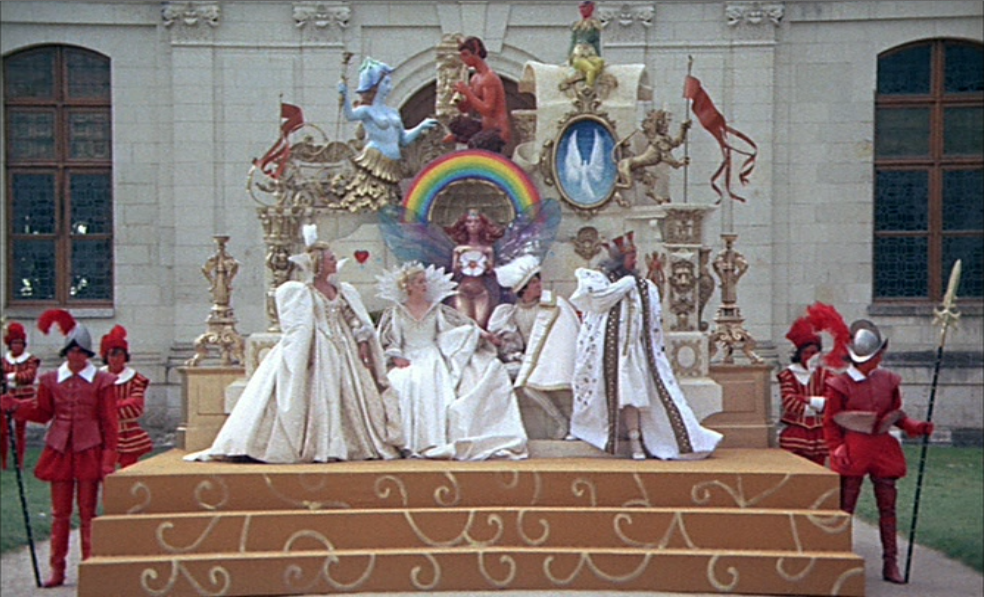

Where to begin? Let’s start by saying that this has got to be the single campiest film of all time. View, for example, the chintzy costumes and sets, complete with rainbow headboard:

Or this cat bench:

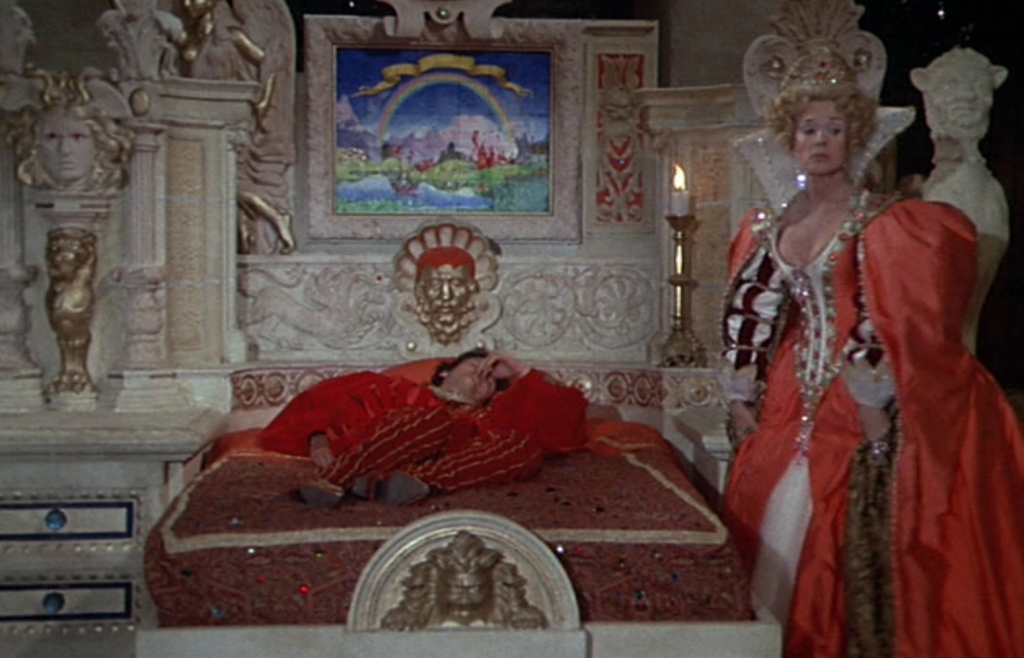

Also, it’s basically Eyes Wide Shut

meets The Smurfs

done on the budget of an average episode of Mr. Rodgers

And a mouth inside an eye inside a rose, because acid flashbacks are so much fun:

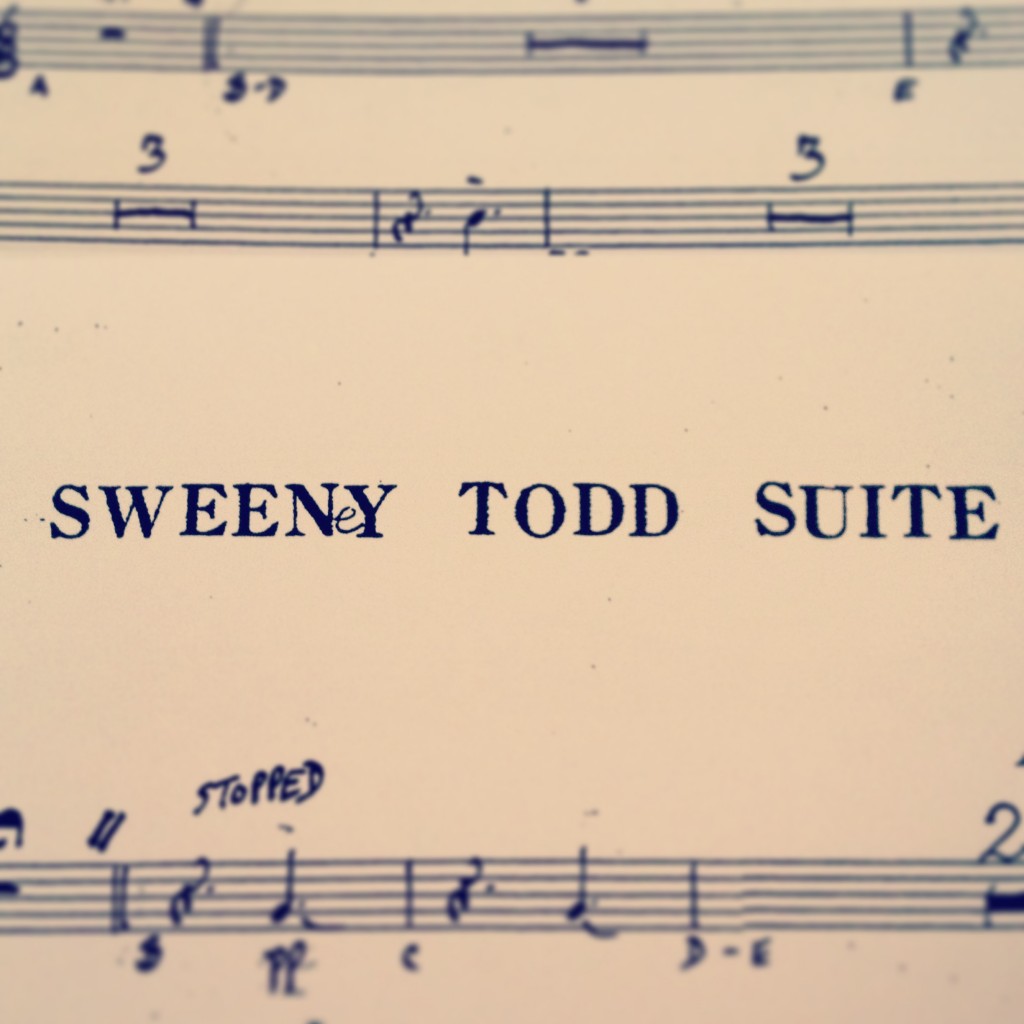

I can only imagine that François Ozon came home from school every day and watched this movie from the ages of about 5-12. Which brings me to the music, because I think Ozon must have forced Phillipe Rombi to listen to the “recipe song” from Peau d’Âne like 20 times before writing the score for Potiche:

I’ve often criticized Michel Legrand for his rather crude job inserting the text of “Les Parapluies” into his pre-existing tunes, but there’s a moment in Peau d’Âne that might just prove me wrong. Listen to his setting of the word “la situation” in both scores:

I’m still right, but they’re very similar, so maybe he had a particular affinity for that word’s melodic qualities.

Finally, this is basically me as I leave the house before every rehearsal:

I feel a little like

I feel a little like