Yearly Archives: 2016

Ask a Maestro: What is Musical Quotation?

Thy King Cometh: 10 year anniversary

Today is Easter, and it happens to be Easter of the year 2016, meaning that this is the 10 year anniversary of my first large-scale professional work, an oratorio called Thy King Cometh. It’s a Purcell meets Sibelius meets Vivaldi meets Ravel kind of Broadway fantasy on Easter themes (well, there’s a Christmas section too, but if you click on the video above, it will start right at the Holy Week stuff.)

I wrote this piece to be performed by the massed musical forces of a little church in the exurbs of Chicago during Holy Week in 2006. I was working as their interim choir director on something like an 8-month contract. Looking back, it shocks me to the point of absurdity that the church’s leadership didn’t bat an eyelid when I told them that I would be composing ALL THE MUSIC for their highest-profile services of the year.

What’s even more galling is how uniquely unqualified I was to write this piece. I knew a little about choral literature, but I was not, as they say, a churched member of the populace. I had just graduated college with a liberal arts degree from, let’s admit it, an overly cerebral university music department. My senior year was spent bathing in Schnittke, Ligeti, and Berio, and I had been banking on going straight into grad school for orchestral conducting.

I didn’t end up getting accepted to any of the masters’ degree programs that I’d applied to, and in many ways this was my first major brush with rejection (hardly my last). In retrospect, I’m glad that it happened right out of the gate, because it forced me to figure out what artistic aims really were as opposed to my career ambitions.

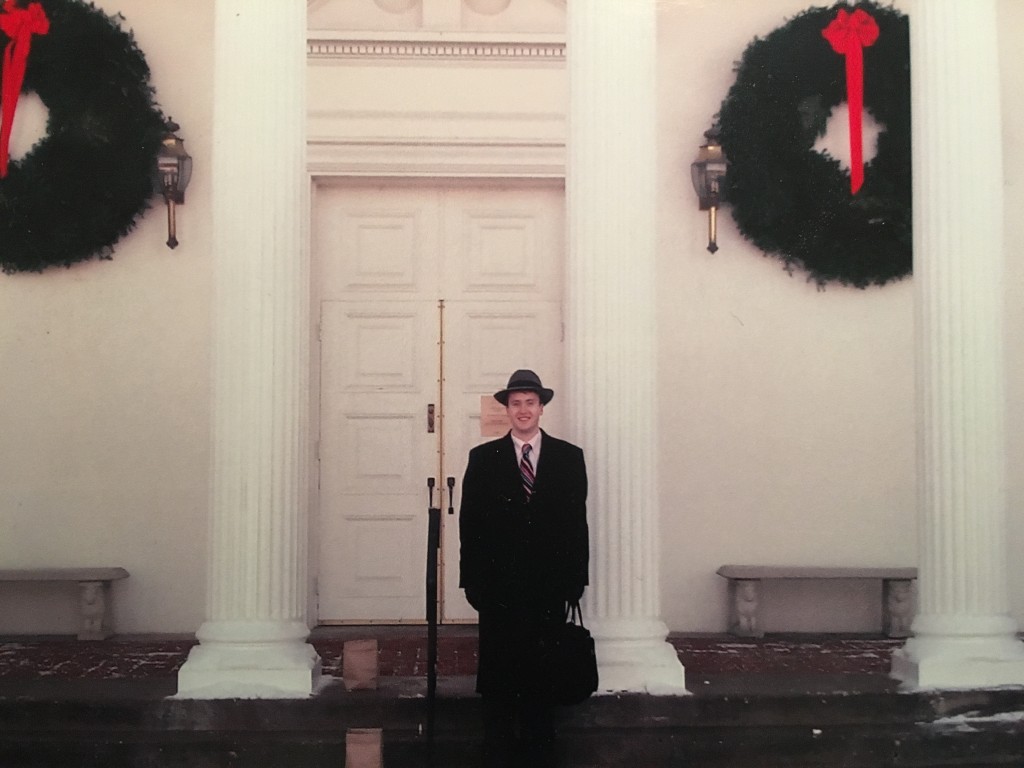

I think I was pretty pleased with myself for landing an actual job though, even my appointment was arranged very ad hoc when a colleague/teacher of mine had to leave on short notice. I actually made a decent little salary and I delighted in being the Golden Boy Choir Director, dressed to the nines every Sunday morning complete with gloves and hat.

But beneath the pastel shirts, I was your typical post-collegiate mess: I was depressed about the grad school thing, I still lived near my old campus, and I spent way, WAY too many nights playing saloon songs in my friend Tim’s frat house basement, cigarette in one hand, whiskey in the other. I have a vivid memory of one Sunday morning when I had to RUN out of the choir loft to the bathroom to kneel before the porcelain altar (“food poisoning”, dontcha know?)

I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but it was time for me to become a man and put away childish things.

I realize now that setting myself the inordinate task of writing so much music in such a short time was my way of accepting the responsibility of my passion for music. It meant that I would honor my relationship with music no matter what the circumstances and better myself as a person to devote myself as fully as possible to that relationship.

And so I got down to business. Many nights I slept on the floor of my office, using the handbell pads for a mattress. I researched theology, biblical history, old and new testament scripture. I cranked out movement after movement, each with a slightly different instrumentation and style, which was another big part of why this piece contributed so significantly to my development as a composer: each piece was a self-contained experiment.

I still love this music, and if I’m being honest, I think the best piece I’ve ever written is the little movement for strings and women’s choir, “And the Lord shall Deliver me” (43:04 above). But the big hits are “Crucify Him” (“Jesus on Trial”), “Thanks be to God!” and of course “Hosanna” (aka “The Triumphal Entry”; watch the 2007 recording session below:)

I’m happy to report these still get performed in churches on a fairly regular basis, and one day I hope to rescore the whole blessed thing for full orchestra.

Also, see that shirt I was wearing in the recording session? It was my favorite. I LOVED that shirt.

Ask A Maestro: What is an A?

fff

ClassicFM posted a photo of Alfred Schnittke’s gravestone on Facebook today. I wrote a thing about it for Brandon Wilner’s fakemusic.org in 2015. Here is a lightly edited version (doesn’t one’s prose always looks worse in hindsight?)

The Soviet composer Alfred Schnittke lived from 1934 to 1998. He was buried in Moscow; his grave is marked with a simple stone, upon which is inscribed a peculiar marking: a whole rest topped by a fermata, marked fff.

The rest indicates silence, emptiness, the absence of sound. This particular rest is a ‘whole rest’: it indicates a silence for the duration of the full bar. Above the rest sits a fermata, Italian for ‘stop’; it’s shaped like a sideways crescent surrounding a dot. In musical notation, a fermata above a note indicates that the note should be held for an indeterminate length of time. (In an orchestral work, the players would watch the conductor in order to cut off the note together).

Taken altogether then, this notation describes a long silence of indefinite measure: the never-ending sleep of the dead rendered in standard Western musical notation.

There is one additional element though, which stands in a contradiction to the above: the three f’s below the whole rest stand for the Italian fortississimo, very, very strong. This is the loudest dynamic marking regularly used in classical music.

We have at least two possible readings:

- That the absence of Alfred Schnittke leaves an excruciatingly loud silence in our world; the loss of his music is a painful maw.

- In spite of his corporeal disintegration, his spirit remains ever present, roaring, and emphatic through his music.

Because this musical marking indicates a ceaseless stream of silence, and because Alfred Schnittke cannot return to the realm of the living (though he did this very thing following his third stroke), Fake Music chooses not to reissue the work so as not to define the parameters of his—or his music’s—rest.