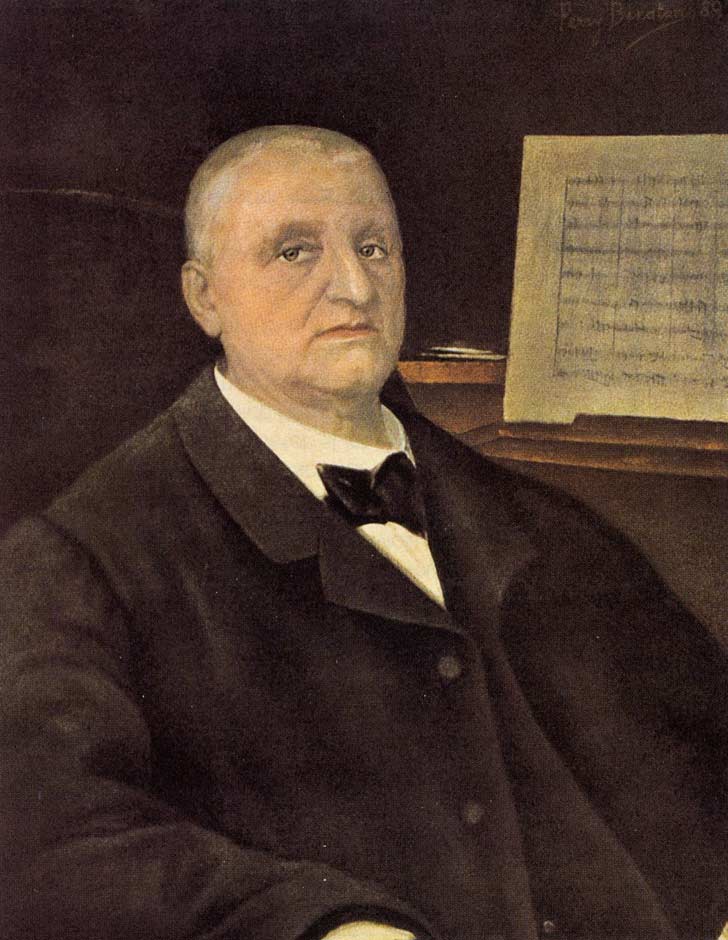

It’s not that I don’t like Bruckner. But it’s not that I do, exactly, either.

If I can get good and steeped in Bruckner’s musical world, for like, even longer than the length of one of his symphonies, I can get into it. But I rarely find that prospect very tempting, because there’s just not enough surface variety or prettiness to coax me down the path to all that depth and beauty.

Which is tantamount to admitting that I’m shallow, and, OK, guilty as charged. But I like to think that I’m maybe a little shallow and a little deep all at once, and there are a number of composers who know just how to calibrate that the spoonful of sugar with the medicine going down.

Johannes Brahms is, of course, the paramount example. On the other side of the spectrum from Bruckner would be, say, Tchaikovsky, whose music definitely errs on the side of aural ravishment rather than emotional honesty.

That doesn’t quite get the dichotomy though, because Bruckner’s music can, in a way, be aurally ravishming as well. It’s more so that Tchaikovsky’s music (and Brahms’, Beethoven’s, et al.’s to various extents) is performative music, whereas Bruckner’s just is. That is to say, when Tchaikovsky gives you grief or joy, it’s often not the genuine article as much as it is the performance of those things.

Another way of saying it might be that Tchaikovsky’s music is, in a sense, the actor upon the stage. Whereas Bruckner’s music just is.

Which is surely a great and noble and virtuous achievement, and why Bruckner’s devotees are quite so ardent. But is it a crime for me to wish for a little wit with my joy? A little melodrama with my sadness? For a little fun every now and again?

I don’t mean to take anything away from Bruckner (not that I could if I tried.) His melodies and textures are often gorgeous (even if his handling of said material is just as often perplexing and aimless. Exhibit A: this 12-iteration https://www.willcwhite.com/audio/bruckner%20sequence.%20Adagio_%20sehr%20feierlich%201.mp3

I’m sure I’ve earned the scorn of the Brucknerian Horde. So please, do your worst.

[Also worth noting for people who are as shallow as I: the google image search of “Bruckner” brought up images of a certain Aaron Brückner, for which you may thank me later.]