It’s been three big projects in as many weeks here at willcwhite inc., all of which – I think – bring up interesting topics for discussion, but we may as well begin with the first one, which involved me revising and re-editing this piece for this performance coming up on September 22 (which, if you happen to live in Chicago, wouldn’t kill you to attend…)

This piece, the so called Fantasy on “Les Folies d’Espagne” is what I would consider my first professional work, my Opus 1, if you will. [Ugh, you guys, should I be using opus numbers? I go back and forth…] Even though I wrote it over seven years ago, the upcoming performance in Chicago will be only its second performance, the major reason for which is that the score calls for prepared piano, harpsichord and portative organ, which, you try finding those three instruments in the same room! I would have performed it myself several other times were it not for the fact that amassing all those keyboards is such a hassle.

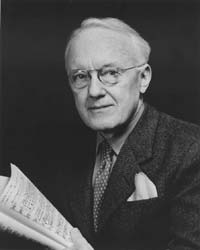

My task in getting ready for this performance was to update the score and edit the music, on which much more below. Some of the changes I wanted to make were based on my own long-held dissatisfactions with a bar here or there, but others were based on comments I received about the piece shortly after I had written it, in that period when a young composer proudly shops around his latest achievement and seeking approval and guidance from his elders in the field. I showed it to Easley, who seemed to enjoy the more impish, comedic moments, but told me to change a note in the viola part to make the chorale more consonant. Later that summer, I showed it to Claude Monteux whose basic feeling was that the piece was “really wild”, and who told me that one of the rit.s should be a subito meno mosso. This past week, years after the fact, I incorporated both of their changes.

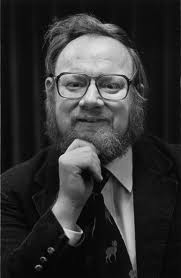

But now, picture this third such encounter, on a cold February day in 2006, in a small music classroom at the University of Chicago. The quasi-illustrious composer John Eaton had come to give a masterclass at the university where he once taught, in which a small group of student composers were invited to present a recent work and receive words of wisdom from the master. Just the sort of thing that I was looking for. The master turned out to be a strange little man who spent the first hour of this hour-and-a-half-long seminar playing – at maximum volume on the tiny classroom’s sound system – one godawful cacophony after another from his renowned catalogue of chamber operas, the playing of which clips was punctuated only by the master’s trips to the bathroom at 10-15 minute intervals.

Finally it came time for Mr. Eaton to hear one or two of the student compositions. A young doctoral student offered a short movement for string quartet. This, the master regretted to say, was not a piece of music, but rather a technical exercise. A burn no doubt, but one couldn’t help but agree. Thinking that there would only be time for my piece if we started right then, (and in spite of the fact that I had already graduated and had weaseled my way into the seminar) I piped up next.

We listened to the whole 13 minutes of my piece, which, let’s just get it out there right now, is sort of an oddball, and certainly features a wide variety of musical styles that John Eaton had clearly worked at length to distance himself from in his own work. The master sat there, flummoxed, for a good 10 or 15 seconds before beginning to sputter out the beginnings of various disapprobations, finally working himself up into a tizzy and shouting, “well, the orchestration’s not very good,” and proceeding to point a measure in which he could not hear the flute in it’s lowest tessitura.

I, of course, calmly accepted his criticism, but really, this wasn’t what I wanted to hear because a) I thought the piece was pretty well orchestrated (I still do) and b) when you present a work at a seminar like this, especially when pressed for time, isn’t the master-composer supposed to give a more general analysis of the big issues that the work presents? Couldn’t he say something about the form, or the twisted mélange of styles, or all of those ridiculous keyboard instruments shoved into one piece?

In the end, his haranguing me over one minor detail at the expense of the larger picture probably said more about his opinion of the larger picture than a more direct approach would have. But still, that’s seriously weak and not much help to a young man in search of serious criticism.

The point of this story really wasn’t supposed to be ‘John Eaton is a self-centered asshole’ (considering that he’s a composer, isn’t that basically a given anyway?)Â I think it was more supposed to be about the things that stick with a young composer as he brings his first major creation into the world, but I’ve sort of lost that train of thought, so the former moral will have to suffice.

I had to edit a lot more than just an occasional viola note or tempo indication over the past couple weeks, because you see, when I wrote this piece 7+ years ago, I was a senior in college, and I was awfully precious about typesetting the scores and parts of my pieces, but I wasn’t so concerned with the practicalities of actually “reading” the “music”. Seven years later, I’m still very precious about the visual presentation of my music – maybe even preciouser – but I like to think that I’ve come a long way in matters of clarity.

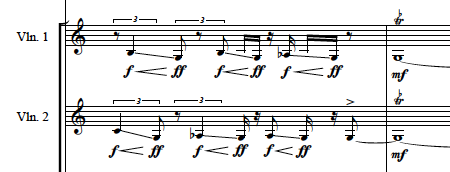

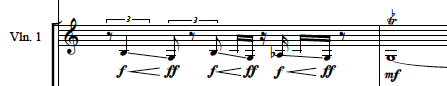

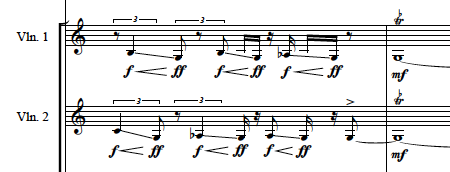

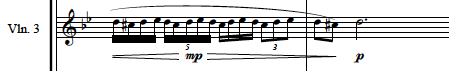

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about. What is now this:

once looked like this:

which, can you even imagine being one of the second violinists – sharing the same part, no less – confronted with those two bars? I cringe.

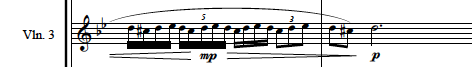

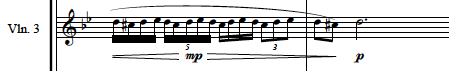

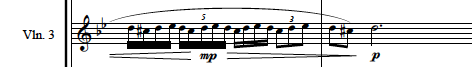

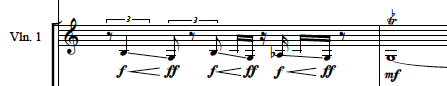

It only gets worse. For, example, there’s this monstrosity:

which now, thankfully, looks like this:

and which I freely admit is still pretty difficult to decipher, but a musician might at least have a fighting chance of figuring out what the hell is going on.

As difficult as parsing out these co-staved parts was (like separating Siamese twins, I tell you!), there’s a good 5-10 additional editorial decisions that had to be made in each of those excerpts. Take this line

First off, there’s the matter of tuplets: should the numbers ‘5’ and ‘3’ go above or below the staff? Traditionally, they go on the beamed side (so, in this case, below), but when I wrote this piece, I was very much in the thrall of Cliff Colnot’s rules for musical typesetting which state that dynamics are the only thing that go below the staff (I have, by and large, remained a faithful adherent to these rules.)

And then take the slur and the crescendo, which carry over from the previous system – should those begin where the first note begins or at the edge of the staff (as they do now)? Should that crescendo be tighter so that it matches the diminuendo? These two bars could look considerably different

but still express the exact same musical idea.

Or in this case

what’s the best way of indicating the empty space wherein a glissando occurs? Is it worth notating that each of those crescendi starts at f and ends at ff? Is that even an editorial question, or a compositional one? Does it just add too much clutter to the page to include the dynamics? And in the second bar there: there’s a trill over a tied note value. Should there be a squiggly to show that it lasts the whole duration of the tie?

These are the questions that regularly vex music publishers and self-published composers, (or else it’s just me.) I have a feeling that most performers never give any thought to how much time goes into avoiding those pesky “collisions” between stems and dynamics, tuplets and slurs, etc., but such things are the bane of the composer’s very existence! Wah.

After all of this work, I really think you should go to this concert, btw.

The five years he spent engaged in litigation revealed the ugliest, least redeemable sides of Beethoven’s personality. In the days leading up to his brother’s death from tuberculosis, Beethoven strong-armed his brother into granting him sole custody of the child on multiple occasions, only to have his brother revert his will back to co-guardianship between Beethoven and Johanna in moments of lucidity.

The five years he spent engaged in litigation revealed the ugliest, least redeemable sides of Beethoven’s personality. In the days leading up to his brother’s death from tuberculosis, Beethoven strong-armed his brother into granting him sole custody of the child on multiple occasions, only to have his brother revert his will back to co-guardianship between Beethoven and Johanna in moments of lucidity.