Hi blogfanz – I’m back, and I’m glad to be returning to our top 10 top 10 with List #8, the Top 10 BEST Composers, where by “BEST” we mean something along the lines of “Most Technically Accomplished”.

“Compositional technique” is a phrase that gets bandied around a lot (among a tiny, tiny élite of classical musicians and critics). But I don’t think I’ve ever heard it defined. Composers confront a series of Design Challenges and Execution Challenges as they write a piece. So, is a composer’s technique simply a question of how well he or she executes a given design? Is it possible to separate the design from the execution?

My favorite example of this conundrum is Gordon Jenkins, a composer/arranger from the Golden Era of pop music who wrote beautiful, lush arrangements for Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Judy Garland, et al. As a composer, he specialized in writing “concept albums” for many of these collaborators.

His concepts for these albums were, in a word, ludicrous – Frank Sinatra taking a guided tour of outer space, for example. But the music he wrote to accompany his zany scenarios is gorgeous. It’s like, “yeah, if Frank Sinatra took a space ship to Saturn and then sang a jig about it, this is the best possible version of that jig.” You know?

Here’s what I came up with. We’ll talk more about the criteria at the end:

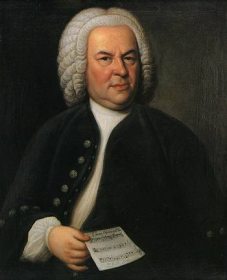

1. J. S. Bach (1685 – 1750)

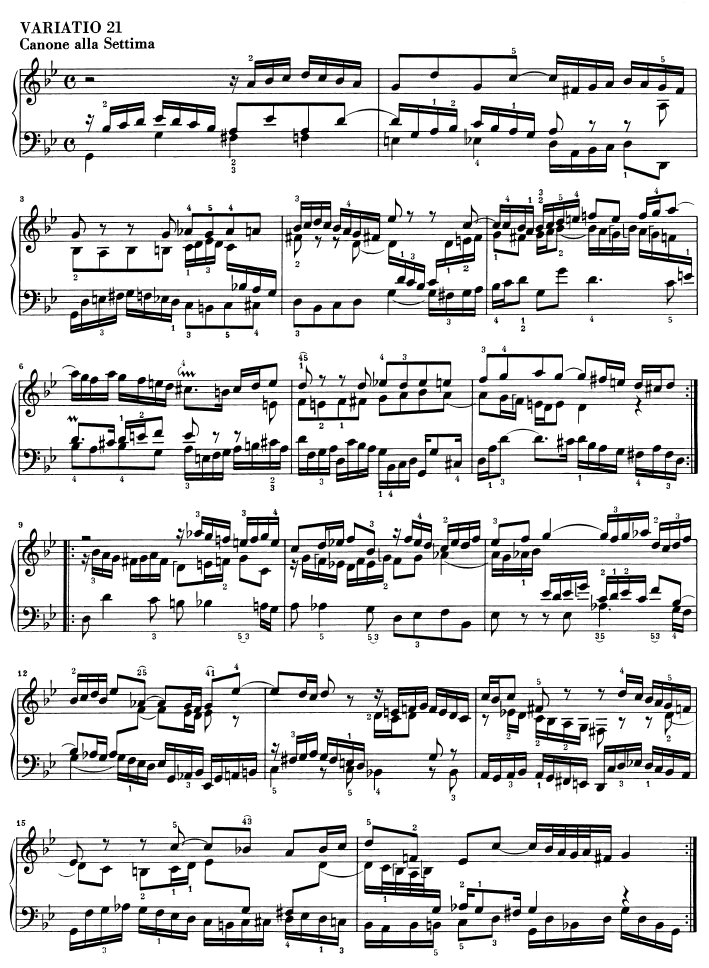

Any person who writes a canon at the 7th, smoothly and gloriously, you do not mess with this person.

(Goldberg Variation 21, Glenn Gould ’54)

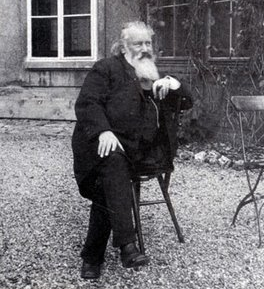

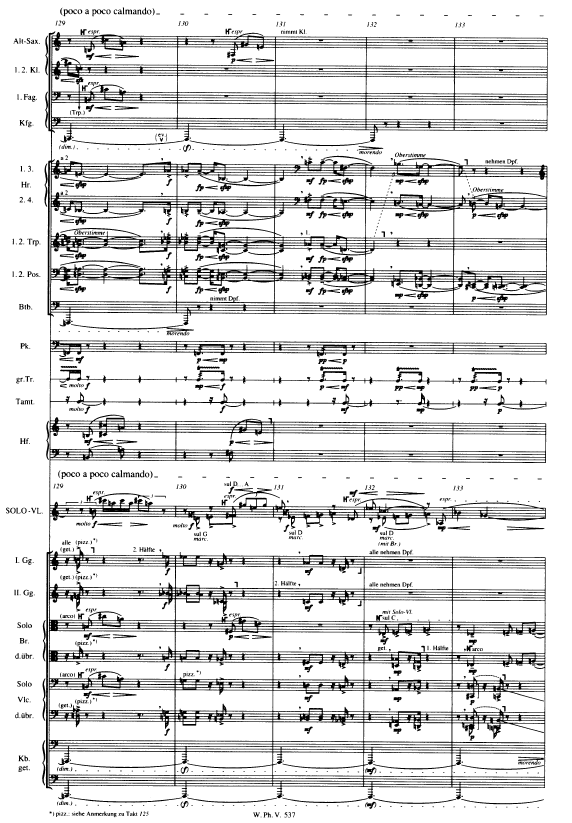

2. Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897)

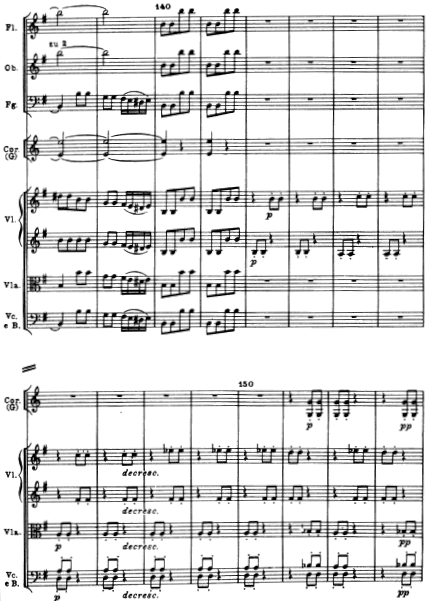

Here’s some mad compositional technique: Brahms’ Symphony No. 2, second movement, letter D. This audio begins 4 bars before the printed excerpt. Here’s what happens:

00:00Â Impassioned 2-part counterpoint; violins v. lower strings; build-up to

00:11Â The previous two lines are remixed into one, and this composite line is pitted against itself; build-up to

00:21 Dramatic tremolo in strings, winds play the main motive (ascending 3-notes), trombones recall the main motive from the previous movement of the symphony.

00:32 Letter D:

Violins and bassoon play the counterpoint from the beginning of this movement, flute and oboe keep playing the motive from the last section, long tones in the lower strings build drama and tension into

00:48Â Parallel section to 00:21

This is what we call ‘tightly constructed’ – the themes all relate to each other, play against each other, appear and reappear, and build up into a large scale structure. But honestly, you don’t have to appreciate ANY of this to enjoy the symphony. This wealth of composerly technique is in the service of beautiful, dramatic, and emotional musical story-telling.

3. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

I say we let Lenny sort us out on this one:

4. (F.) Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809)

Now, a lot of the tricks that Lenny was just talking about w/r/t Beethoven, I’m convinced Beethoven learned from Haydn. That is to say – the guy (Haydn) was killer when it came to form. But he (Haydn) also happened to be really good at all the things Lenny claims Beethoven sucked at: melody, harmony, fugues, etc. Haydn dazzles us, leaves us spinning, and has a ball doing it.

So for all his fancy tricks, I’m going to present a passage that seems rather mundane – just 8th notes, in pairs. The trick though, is that he slowly modulates the harmony, dynamics, and instrumentation to bring us back to the opening theme of this, the last movement of his 88th Symphony:

(score picks up on 00:04)

It’s like you’re driving around some back country roads, and just when you think you’re totally lost, you look up and it turns out you’re back where you started. That’s Haydn.

5. Johannes Ockeghem (1420ish – 1497)

I’m hardly an expert on this composer or his music. But like many an undergraduate music major before and since, I did at one time learn about the staggering contrapuntal accomplishments of Flanders’ greatest son.

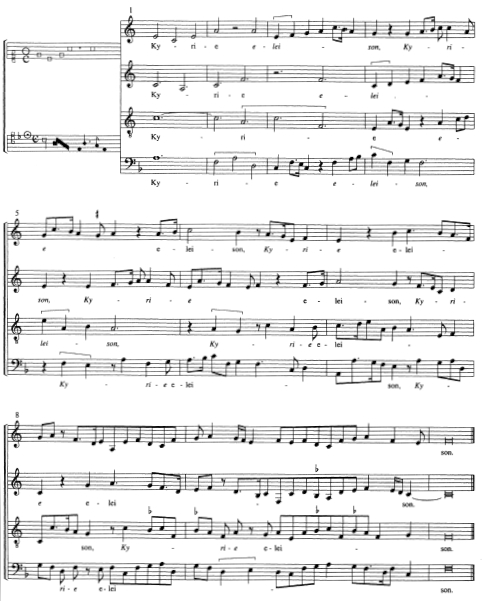

Let’s look at his most famous work, the Missa Prolationum, so called because of its extensive use of “prolation canons”. It works like this: you all know what a canon is – “Row, row, row yr boat”, “Frère Jacques”, etc., anything where one guy sings a tune and the other guy starts singing the same tune a little later and it all works out harmonically. Well, in a “prolation canon” (which is more commonly known as a “mensuration canon”), the two guys sing the same tune at different speeds. Normally, they have a relation to each other – like twice as fast or twice as slow.

They don’t always have to stagger their entrances either – they can both start singing at the same time and it still counts. Ockeghem took this idea of mensuration canons to the extreme. Here’s the Kyrie II from his mass. There are two melodies: one in the soprano and alto, and another one in the tenor and bass. The soprano and alto sing their melody at different speeds. The tenor and bass sing their melody at two entirely different speeds. What’s more, the two melodies are very closely related.

You try to do that.

6. Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918)

I’ll turn over the floor again, this time to Esa-Pekka Salonen:

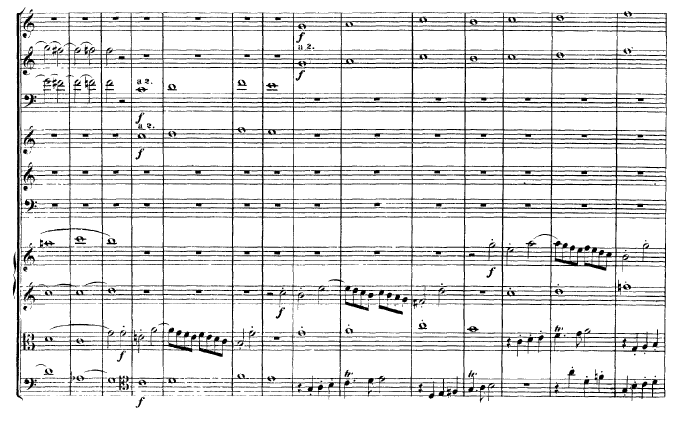

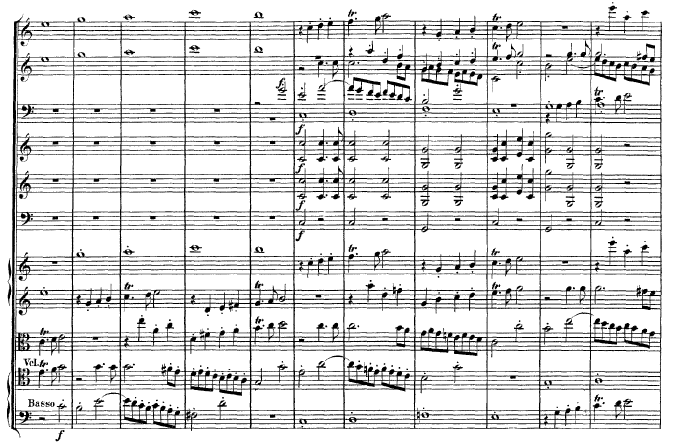

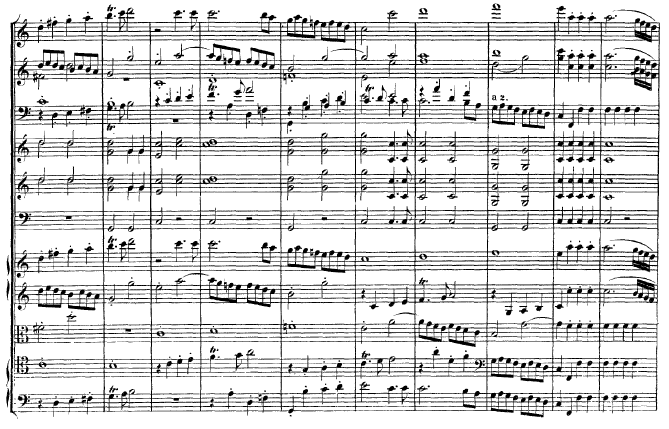

7. Wolfgang Amad̩ Mozart (1754 Р1792)

I don’t know where to even begin talking about Mozart’s ridiculous compositional technique, but you can’t do much worse than the final set of canons in his last symphony, No. 41 (the “Jupiter”). This piece is chock full of canons, fugues, and other contrapuntal devices – and yet, you never get tired of them (unlike, let’s admit it, Bach). It’s just one vivacious bar after another:

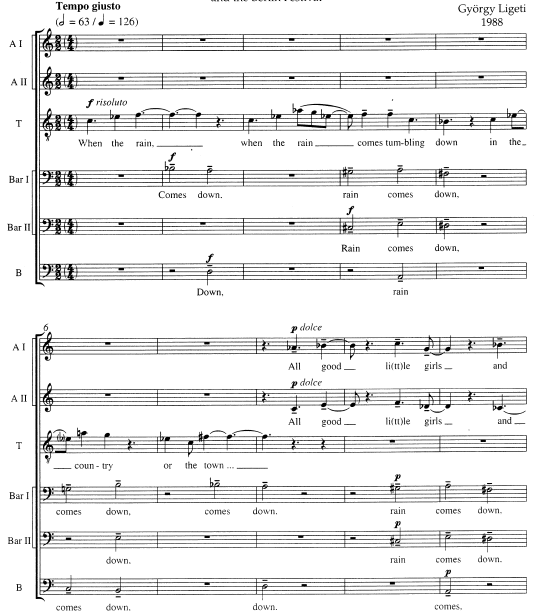

8. Gy̦rgy Ligeti (1923 Р2006)

With a mind to the generalish audience that sometimes reads this blog (if anyone’s actually made it this far), let’s turn again to the Hungarian composer’s Nonsense Madrigals, based on texts by Lewis Carrol.

Here’s “Flying Robert”:

So what makes this so great? Well, first off, let’s figure out what’s going on.

Element the first: The tenor has a melody (“when the rain… when the rain comes tumbling down… in the country or the town”). Each of the three phrases of the melody begins the same and builds to a higher note. The rhythm of the melody is irregular – it has a rhapsodic quality.

Element the second: This piece is a passacaglia, which means there is a repeated, regular figure in the bass line. Ligeti does that and also includes the two baritones in establishing the pattern. So even though this pattern gets shifted from beat to beat, there is a regular pulse going on, grounding the music.

Element the third: When the altos come in, they pick up the tenor’s melody, but their rhythm mimics the regular pulse of the passacaglia people, but shortening their pulse by 1/4 of the value. Just to make things a little more complicated, at the top of the third system, the second alto starts drifting off into his own little world.

So again, what’s so great about this? It’s that Ligeti combines the elements in a way that gives the listener a simultaneous sense of regularity and irregularity – everything sounds natural but odd, logical but unpredictable. It works like a precision machine, as does much of his music, including the wild, 100-instrument scores from his early period.

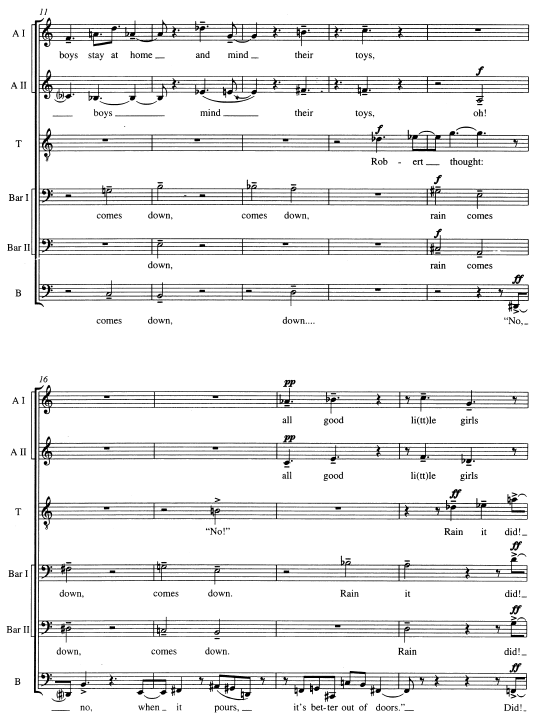

9. Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971)

I’ll admit, there’s occasionally things that are clumsy in Stravinsky’s writing – some of his meter and barring choices can be rather confusing at times – but the flaws are very minor, and easily overlooked when taken in context of his overall skills as a writer of music.

Since fugues seem to be a common theme of this list, here’s a great one:

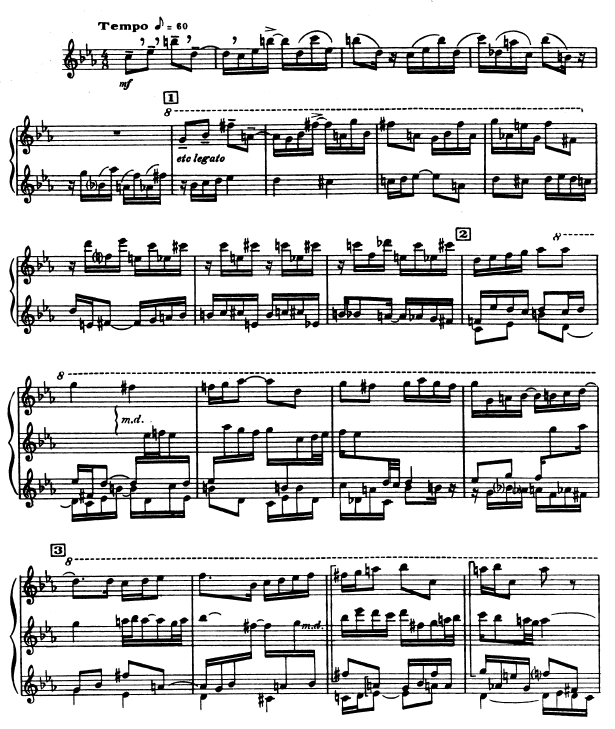

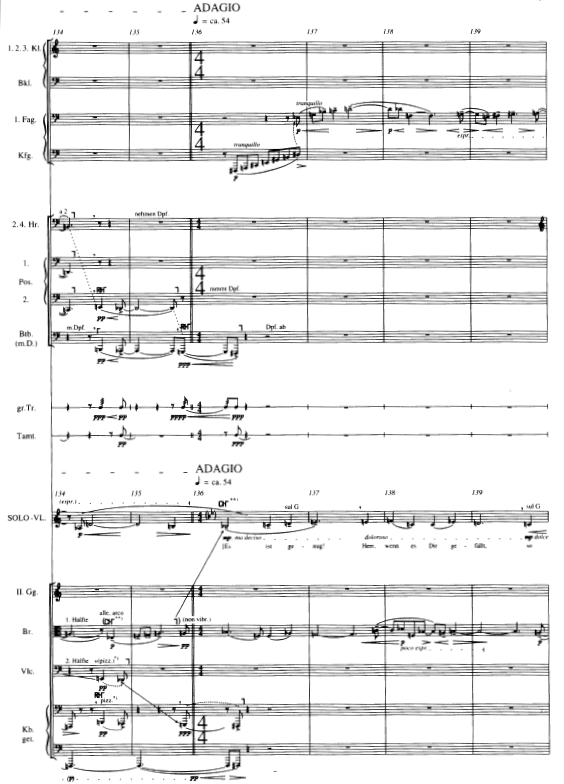

10. Alban Berg (1885 – 1935)

Alban Berg, the shining light of the Second Viennese School, has gotten all too little love up in these lists so far. Finally, we’ve arrived at his category.

Alban Berg, the shining light of the Second Viennese School, has gotten all too little love up in these lists so far. Finally, we’ve arrived at his category.

What I personally find so impressive about Berg’s writing is his ability to unite disparate elements. He chose to use a wide range of compositional tools: tonality, atonality, dodecaphony. He wrote waltzes and polkas, but infused them with eerie harmonies. He wrote startling, arhythmic sound masses and contrasted them with delicate, crystalline chords.

His opera Wozzeck is practically a textbook of compositional forms. But I’ve chosen the most famous passage from his Violin Concerto to illustrate how he so skillfully combined vastly different musical worlds:

Berg’s going from a huge dissonant cluster to a quotation of Bach. What’s admirable is the smooveness with which he does it: the chorale melody starts with a rising 4-note motive. He introduces this motive in the violin during the most dissonant music. Then he gives us the tune, but it’s set against slightly less dissonant music. By the time the winds enter on Bach’s harmonization, it makes all the sense in the world.

Discuss

So, in choosing the composers on this list, I think I settled on the following criteria for great compositional technique:

1) handling of counterpoint (multiple, simultaneous lines)

2) tight motivic construction (building melodies and sections of music out of small themelets)

3) form (a logical succession of musical ideas, paced correctly so that the music seems to follow a logical flow)

4) ability to contrast and unite disparate musical ideas (which nobody does better than Schnittke, and I hate not including him on this list)

And then there’s the matter of, given their resources, how well did these guys write the stuff down on a score? Sibelius is one of my favorite composers, but his scores are a certifiable mess when it comes to logic and consistency. Ligeti’s scores are nearly as virtuosic in their meticulous layout and instructions as they are in their musical content.

So, y’all, what do you make of these criteria? And who fits it? My guys, or some other peops?

If you’ve made it this far, it’s time to let your voice be heard in the comments section!

Monsieur Dukas personally had a lot to do with his status as a one-hitter – like Brahms before him, he was such a perfectionist that he ended up destroying many of his works. With only a handful of published pieces, the odds were very low that any one of them would hit it big.

Monsieur Dukas personally had a lot to do with his status as a one-hitter – like Brahms before him, he was such a perfectionist that he ended up destroying many of his works. With only a handful of published pieces, the odds were very low that any one of them would hit it big. I couldn’t NOT include Pachelbel on this list, but I could at least make him last. Any string players reading this will know the reason for my ‘tude re: Mr. Pachelbel: we have been forced to play his mega-hit Canon in D at least since we were in middle school, but it feels more like since the dawn of time.

I couldn’t NOT include Pachelbel on this list, but I could at least make him last. Any string players reading this will know the reason for my ‘tude re: Mr. Pachelbel: we have been forced to play his mega-hit Canon in D at least since we were in middle school, but it feels more like since the dawn of time.