I’ve kind of been stalking the Chicago Symphony recently. Put another way, the orchestra has recently held three free events to open up their season, and I’ve been to all of them. Two of them were hits – out of the ballpark we’re talking here – and one was a miss.

Thursday, Sept 16

Mexico 2010 celebrations

Benito Juarez High School Auditorium

Carlos Miguel Prieto, conductor

This event was part of the CSO’s contribution to Mexico’s bicentennial celebration, and important collaboration and outreach event given the large Mexican community in Chicago and given the fact that Chicago is a sister city with Mexico City. The programming was awfully clunky though – why did it begin with “Till Eulenspiegel”? Why not just, you know, Mexican music? That’s what followed, namely Galindo’s “Sonnes de Mariachi”, Marquez’ “Danzon No. 2” and Moncayo’s “Huapango”.

Let’s forget this German oddball pink elephant gargantuatron in the room for a moment (which I’m guessing might have been the idea of the conductor who wanted to get something juicy into a rare appearance with the Chicago Symphony) and look at the Mexican selections. I happen to have played all three of those pieces in orchestras at one point or another. I’ve also played really, really good Mexican music. If you were going to play Mexican music for an inter-generational, celebratory crowd, how could you possibly avoid doing Sensemayá, which is one of the baddest pieces of orchestral music Mexican or otherwise out there?

[part 2]

I’m basically just shocked that there was not a single piece by Ravueltas (above) or Carlos Chavez, who are justifiably considered Mexico’s great composers. I also hate to rag on this concert because it did seem to deeply affect the community in attendance – young and old, Hispanic and non-, all seemed genuinely moved that their new auditorium would be graced by the presence of this great orchestra, and that’s a good thing.

Sunday, Sept 19

Free Concert for Chicago

Millennium Park

Riccardo Muti, conductor

Here was an amazing concert – everything was just right. First off, the orchestra sounded fantastic, like a real old orchestra with beautiful, singing tone. A huge part of the equation was the programming, which was very much (and very wisely) of the “give them what they want to hear” variety: Verdi’s Overture to La Forza del Destino, Liszt’s “Les Préludes” (OK, nobody’s perfect), Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet, and Respighi’s The Pines of Rome. All were appropriately flashy and bombastic, but for me, the Verdi stood out particularly in terms of sound and interpretation – just perfect.

The other cool thing was how crowded it was there. It literally felt like a rock concert wending one’s way through the unwashed masses at the park.

And at the end? Fireworks!

Wed, Sept 22

Dress Rehearsal for the Opening Subscription Concert

Orchestra Hall

Riccardo Muti, conductor

Here were the real fireworks (umm… you know, figuratively speaking). First half: Berlioz, Symphonie Fantastique. Second half: Berlioz, Lélio.

What is Lélio, you might ask? Well, that’s a question easier asked than answered. It’s the sequel to Symphonie Fantastique. [btw, I find the idea of a purely instrumental work having a “sequel” incredibly interesting – I can’t think of a single other example. Can you?] It’s a sort of monodrama for narrator, orchestra, chorus, and lieder singer with accompanist. There’s a huge amount of dialogue given by the narrator (in Chicago played brilliantly by a truly corpulent Gérard Depardieu:  )

)

The narrator is sort of Berlioz, but sort of not – basically, it’s whoever wrote the Symphony Fantastique – let’s call him Berlioz’s alter ego. [p.s. here are some notes that I put up about Symphonie Fantastique a while ago.] This has got to be the most Berlioz-y piece that Berlioz ever Berliozed, if you’ll pardon the expression. Basically, the narrator extemporizes at length about his ordeal in composing/living the story of the Symphonie, the inability of his continental peers to understand Shakespeare’s brilliance, and his mental cohabitation with the characters from The Tempest – all interspersed with orchestral interludes, lieder played at the piano, and a choeur des ombres. Towards the end, it turns out that the composer-narrator just happens to have sketched a choral-orchestral fantasy on the subject of The Tempest, and – how convenient – there just happens to be an orchestra on stage. Before the piece begins, he exhorts the players on stage to play in tune, follow the conductor, not to drag, etc. This lengthier piece is what one usually hears from Lélio. The “Tempest Fantasy” ends and the narrator is quite impressed and then goes off to die – or something.

Anyway, I’ve got to hand it to Muti – this is a hell of a way to kick off a season. Great mix of a familiar classic and something crazy. New York should be green with envy. Their opening concert sounds like it SUCKED!!!!

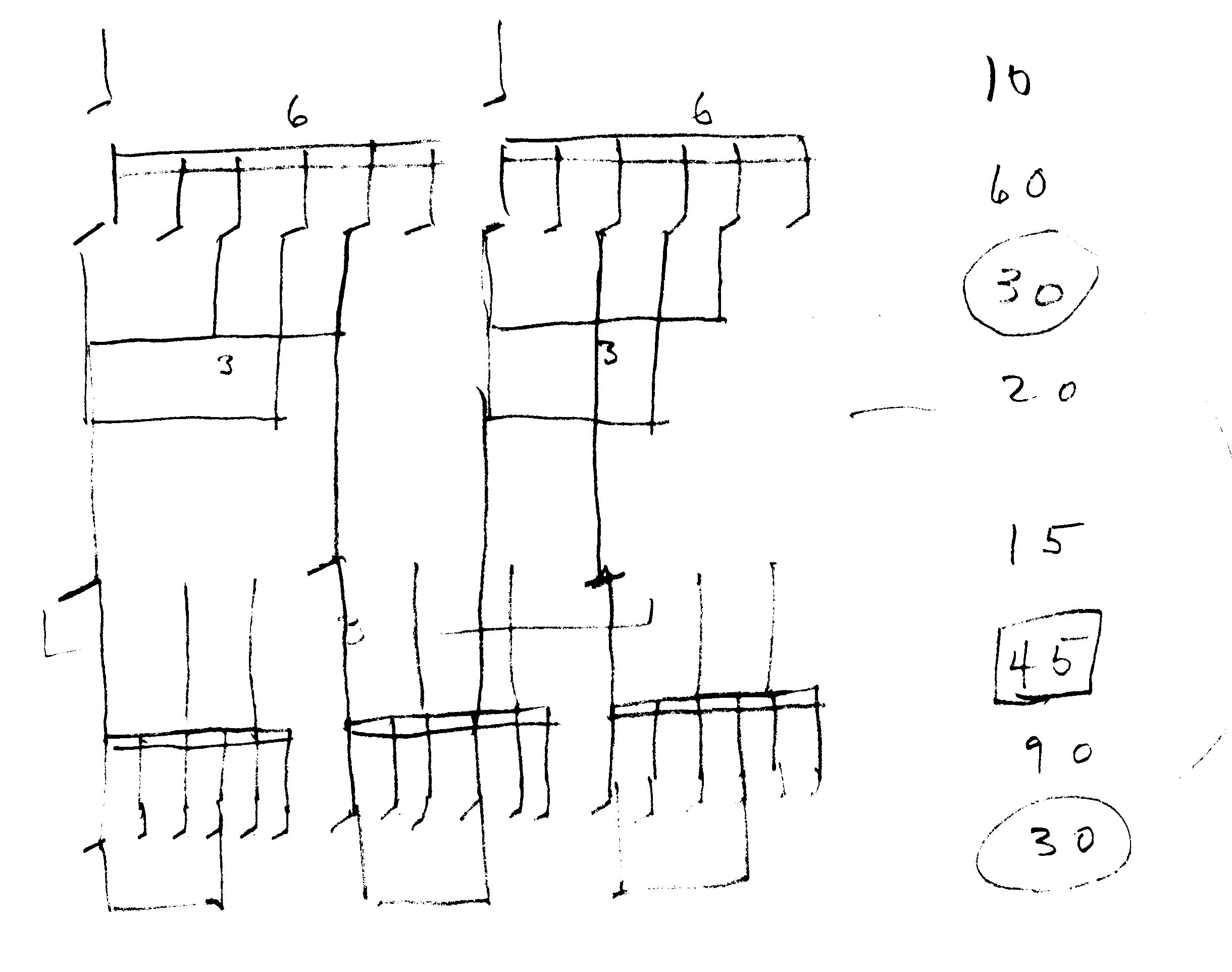

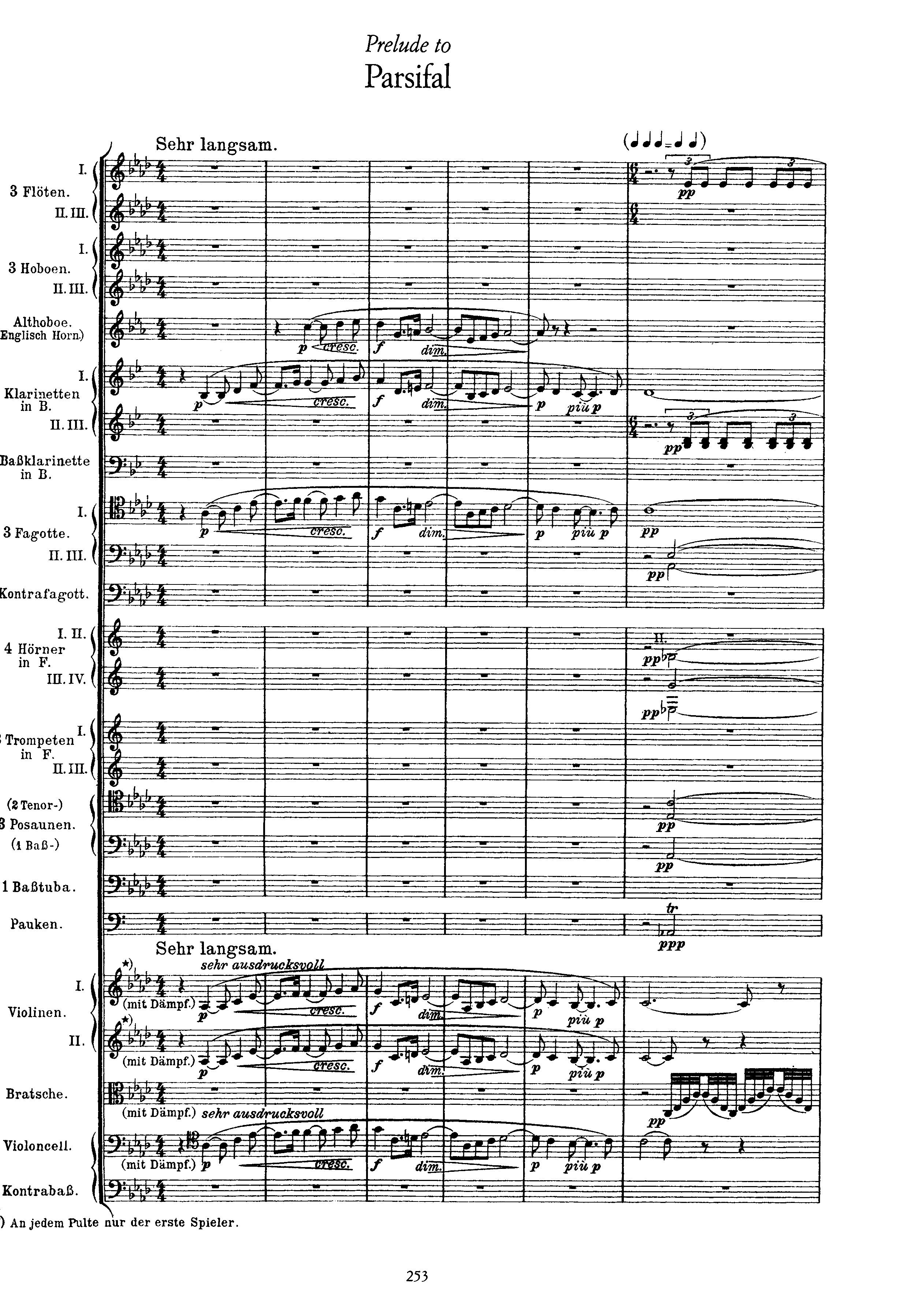

we notice that the second beat in this pattern consists of 2 eighth notes. So, one solution is to approximate the triplets and make sure that the second eighth lands on the conductor’s fourth beat. 1 eighth note = 1.5 of the triplets; therefore 3 triplets + 1 eighth equals 4.5 triplets.

we notice that the second beat in this pattern consists of 2 eighth notes. So, one solution is to approximate the triplets and make sure that the second eighth lands on the conductor’s fourth beat. 1 eighth note = 1.5 of the triplets; therefore 3 triplets + 1 eighth equals 4.5 triplets.