Dynamics are really a blunt set of tools composers have to shape and shade what is supposed to be the most ethereal of art forms. Most of us regularly use about eight markings: ppp, pp, p, mp, mf, f, ff, and fff. Brahms made a valiant effort with pf (poco forte) but it never really caught on. Tchaikovsky made a valiant effort with fffff but now we’re all deaf.

Schoenberg had a great idea with marking lines “Hauptstimme” (main voice) and “Nebenstimme” (next voice), but the whole thing becomes too confusing when try you combine those with the traditionally notated dynamic markings on the page.

Poco forte, btw, is softer than mezzo forte. (I find that most musicians don’t know this.)

A composer has to figure out: at what overall dynamic level should the ensemble should sound? How prominently should x instrument sound within that texture? What effect will the natural acoustic properties of said instrument have in determining its volume? Should that even be taken into account, or should we just go for pure dynamics? Based on the entire history of the literature for their instrument, how are players of x instrument likely to interpret y dynamic?

Jennifer Higdon seems to have this whole thing figured out.

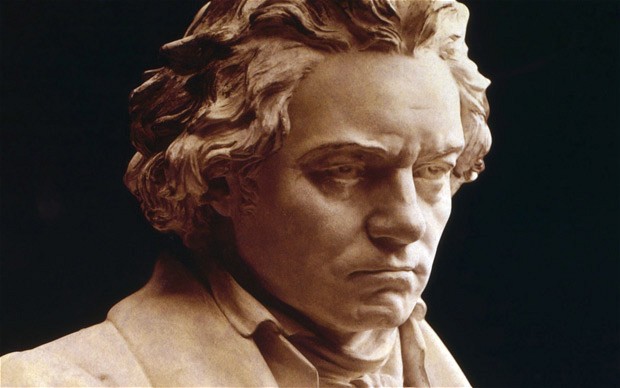

Tchaikovsky was really pretty bad at dynamics overall. Most of the phrasing inherent in his music is in no wise notated by the dynamics (though he did get a lot better at this as he progressed.) I just conducted the 2nd symphony, a charming piece with very sloppy dynamics. Let’s not even talk about the meters.

One of my first composition teachers told me that he would complete an entire piece and then go back and insert the dynamics. This still boggles my mind. Go back and refine dynamics, yes, I usually do that about 50 times. But insert? Interestingly, he believed wholeheartedly that “dynamics really make or break a piece.”

I just conducted Ralph Vaughan Williams’ cantata “Dona Nobis Pacem”. I think the old man spent about 30 minutes TOTAL marking the dynamics. Choral basses, stating the theme of a fugue are marked p with trombones and timpani marked f. This is symptomatic of this piece, which feels hastily assembled and lumpily misproportioned. There are some great passages though.

Schumann is so often criticized for his orchestration. I came of age believing that old lie, and now I’ve totally rejected it. Yes, there’s a lot of balance problems, but most of those occur because he wrote in block dynamics (like… just about every other composer at that time.) Get a decent bunch of musicians together and they can usually figure out what’s going on with their parts. Unlike Tchaikovsky, at least the blocks are correctly dynamicized.

When you’ve got, say, woodwinds playing a chord f and you bring in the trombones mf, how will they know what to do in comparison? Should you write them a little note?

Sure!

Harps should always be marked f (and doubled or even tripled – what can I say, I just love the harp!)