The Dedicatee

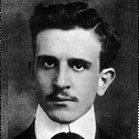

In many ways, we who enjoy the music of Beethoven’s late period owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to an otherwise insubstantial member of the minor nobility. As the sixteenth child of the Emporor Leopold II, Archduke Rudolf of Austria could be pretty well certain that he was not going to inherit his father’s title, land, or fortune; as such, he did what so many younger sons of the nobility did and went into the priesthood, becoming archbishop (and then Cardinal) of Olmütz in 1819.

Rudolf seemingly got a pretty sweet deal, because while his older brother went down in history for losing his empire to Napoleon, Rudolf began studying piano and composition with the most famous composer in Europe, Ludwig van Beethoven.

Though Beethoven complained about his obligation to give the Archduke daily lessons (sometimes lasting more than two hours), the two grew to be friends at a time when Beethoven needed friends most. Napoleon’s wars had caused many of Beethoven’s most reliable patrons to abandon imperial Vienna for fear of losing their heads. Beethoven had insulted, cheated, or otherwise alienated the majority of the princely families who remained in their Austrian palaces.

The Lawsuit

It wasn’t just other people’s families who Beethoven alienated. The death of Beethoven’s younger brother Kaspar in 1815 precipitated the ugliest, most productivity-stifling event in his life: the fearsome custody battle he waged against his sister-in-law Johanna for the guardianship of his nephew, Karl.

The five years he spent engaged in litigation revealed the ugliest, least redeemable sides of Beethoven’s personality. In the days leading up to his brother’s death from tuberculosis, Beethoven strong-armed his brother into granting him sole custody of the child on multiple occasions, only to have his brother revert his will back to co-guardianship between Beethoven and Johanna in moments of lucidity.

The five years he spent engaged in litigation revealed the ugliest, least redeemable sides of Beethoven’s personality. In the days leading up to his brother’s death from tuberculosis, Beethoven strong-armed his brother into granting him sole custody of the child on multiple occasions, only to have his brother revert his will back to co-guardianship between Beethoven and Johanna in moments of lucidity.

Beethoven’s initial reaction to his brother’s death was to accuse his sister-in-law of murder by poisoning. When this turned out to be a dead end, he began the battle for sole custody of Karl. He won decisive early victories against his sister-in-law in the Landsrecht, the court of the nobility. Beethoven’s fates reversed in 1818 when he accidentally let slip in the course of a deposition that the “van” in his Dutch surname was not equivalent to the Germanic “von” which automatically conferred nobility. As such, his case was sent down to commoner’s court, which was much more sympathetic to Johanna van Beethoven’s cause.

Though Beethoven finally won custody over Karl, his insane, possessive love took a perilous evinced itself again a few years later when the teenage boy attempted to take his own life with a pistol on a high hill overlooking Beethoven’s summer home.

The Second Mass

Though he sometimes played around with themes for decades before turning them into full pieces, the four years it took Beethoven to complete the Missa Solemnis (1819 – 1823) represented the longest sustained period of work Beethoven spent on any single composition. Strangely for a composer who often went back and forth between projects, Beethoven did not work on individual movements and sections simultaneously; he composed it from beginning to end, beginning with the Kyrie and ending with the Agnus Dei.

This was in fact Beethoven’s second setting of the traditional Latin mass text, having written his first in 1807, the lesser known Mass in C. Aside from obvious stylistic differences, the main difference between the two works is length: whereas the Mass in C clocks in at a respectable 45 minutes, performances of the the Missa Solemnis usually last about twice as long.

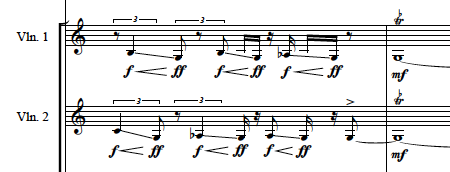

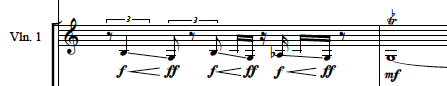

As such, Beethoven languished considerable attention on every word and phrase of the Latin text. [N.B. the “Kyrie” is the only part of the Roman mass not in Latin; it’s in Greek.] Let’s take as an example his setting of the phrase qui sedes ad dexteram patris (“who sits at the right hand of the father”). Here’s how Beethoven set it in the earlier Mass in C:

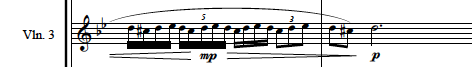

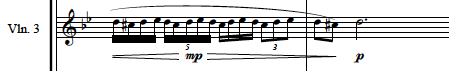

And here it is magnified in every dimension in the Missa Solemnis:

The Difficulties

Beethoven rarely took into account the technical limits of the musicians he was writing for. He was as difficult and irascible a composer as he was a human being, especially when it came to writing for singers. The Missa Solemnis is arguably the most daunting challenge in the choral repertoire. It’s not exactly easy for the soloists or the orchestra either.

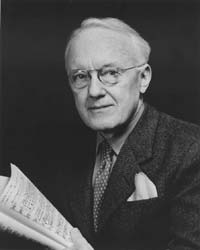

Here is an excellent performance of the Gloria given by the august London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus under Sir Colin Davis. It’s high order music-making, but you’ll still hear the sopranos straining, the orchestra struggling, and the soloists straying from their ideals of intonation. And yet the overall effect is, well, glorious: