I don’t believe there is such a thing as a Good Melody. I almost don’t know what such a thing would mean, because for me, a melody is nothing without a good harmony. Or perhaps I should say, “harmonic progression.” Harmony’s great, but what’s the use of a good harmony without a beautiful melody to glide upon it, to argue against it, to define it, to sing it?

So when people speak of “the Great Melodists,” I think they’re really talking about those people who are masters of uniting beautiful melodies with complimentary harmonies, not just writing tunes. Gregorian chant, which may be considered the purist form of melody, interests me on little more than an intellectual level and rarely moves me beyond a vague sense of the ethereal. There are even certain bel canto opera composers from the 19th c. who wrote grand melodies with attractive features, but who won’t be included on this list in favor of composers who wrote melodies at least as good, and had more interesting harmonies.

The most basic of melodies can be rendered voluptuous when wrapped in a cloak of warm harmonies. Here’s my list of the people who did it best, the third such list in our series. See if you agree.

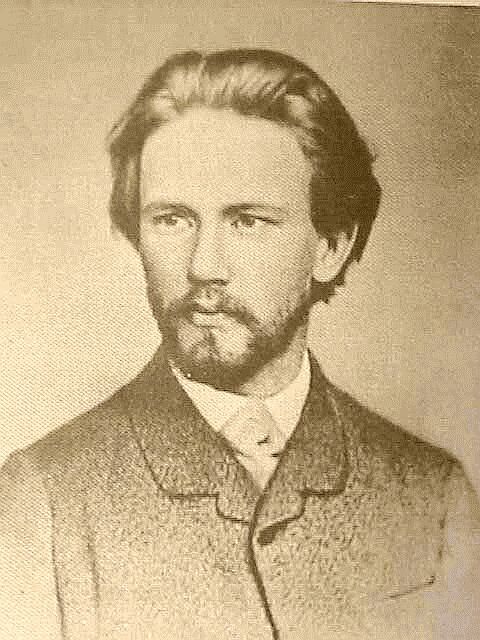

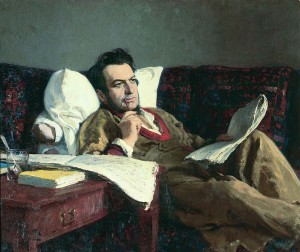

1. Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893)

When you think Tchaikovsky, you think melody. [Of course, really, you think harmonic melody, but I’ll try not to keep dwelling on this point too much.] Tchaikovsky’s melodies are gorgeous, voluptuous, songful things. There are big, sweeping melodies that take center stage. There are also small little melodic fragments that, for some reason, have as much power as most other composers’ biggest tunes. It takes a brave composer to suffuse every bar with melody this way – wouldn’t you be worried about running out?

2. Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943)

You might notice a Russian theme (thème Russe?) developing here. Those Russians sure can write some harmonic melodies. Rachmaninoff adored Tchaikovsky, and it shows. His harmonies are bolder and often darker than his model’s though, and his melodies contain many more surprises.

A lot of people think that beautiful melodies simply spin out from their creators’ hearts. But a great tune is equal parts intellect and emotion. This melody, from Rachmaninoff’s 2nd piano concerto, could end any number of places and be perfectly satisfactory, but through a series of ever more ingenious harmonic tricks, Rachmaninoff keeps this one melodic thread going for over a minute. It rises and falls many times, but it has only one apex point — one note that is the top of the melody’s arc. And, not surprisingly, this is the note with the most color to the harmony, the most poignancy and beauty. Just listen – you’ll hear it about 48 seconds in.

(Piano Concerto #2, Atzmon/NPO, Frühbeck de Burgos)

3. Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924)

Puccini is such an obvious choice because of his lush operatic melodies. And he brings us to another point about the great harmonic melodists, which is that they tend to be loved by the public but disparaged among the musical intelligentsia. What a mistake is made in the groves of academe when the craggier professor types assume that a popular touch comes at the expense of a composer’s craft. At least in Puccini’s case, it’s very much the opposite. He was a genius of harmony, color, and orchestration (much like Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky, btw.)

I think it would take a real cold fish not to get a body high from a passage like this:

4. Richard Rodgers (1902 – 1979)

Of all Broadway’s great composers, Richard Rodgers is the most distinguished melodist. He’s also an excellent example of what this particular list is really about, namely, who could write the best musical material. Beethoven’s melodies can be transcendent at times, but he’s hardly our most accomplished tunesmith. Beethoven’s great strength is the way he used his material. Rodgers, on the other hand, only wrote melodies and harmonies – he didn’t arrange, orchestrate, or write the lyrics for any of his tunes. [Though he certainly benefited from collaborating with one of the most brilliant colorists in the history of Broadway orchestration.]

So I think it’s a real testament to his talents that the melodies themselves are the most distinguished feature of his musicals. Sure, Oklahoma was a landmark in music theater history for its bold exploration of form and artistic integration, but it’s a melody like this that brings tears to your eyes:

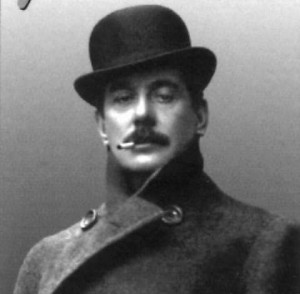

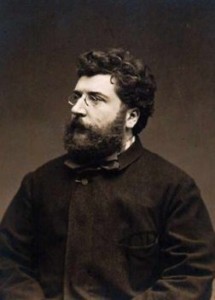

5. Georges Bizet (1838 – 1875)

Not surprisingly, we come to another composer most well-known for his work in the theater. Carmen might be the greatest collection of tunes in opera. Note the distinction — not the greatest opera (though it sure ain’t shabby!), but the best set of tunes as an opera.

Not surprisingly, we come to another composer most well-known for his work in the theater. Carmen might be the greatest collection of tunes in opera. Note the distinction — not the greatest opera (though it sure ain’t shabby!), but the best set of tunes as an opera.

Interestingly, Bizet was a mightily accomplished piano virtuoso, even impressing Liszt at a dinner party with his chops. [You know, his playing. Not his lamb chops -—or his mutton chops, impressive as they may have been.]

Prepare for aural ravishment:

(“L’Arlesienne Suite”, Ulster/Tortelier)

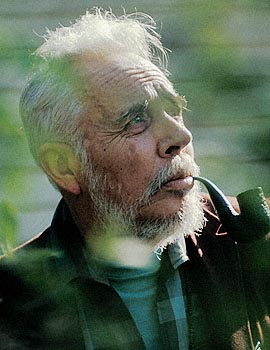

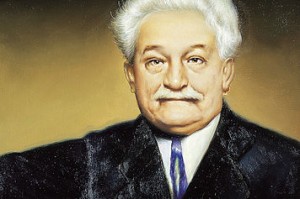

6. Alexander Borodin (1833 – 1887)

The third Russian on our list, Mr. Borodin’s primary vocation was as a chemist (a rather dour chemist, from the look of it). For those who care about such things (or for those who just don’t have time to read the entire Wikipedia article), Mr. Borodin discovered the Hunsdiecker Reaction 90 years before Hunsdiecker. And Hunsdiecker didn’t even write a single quartet. Asshole.

The third Russian on our list, Mr. Borodin’s primary vocation was as a chemist (a rather dour chemist, from the look of it). For those who care about such things (or for those who just don’t have time to read the entire Wikipedia article), Mr. Borodin discovered the Hunsdiecker Reaction 90 years before Hunsdiecker. And Hunsdiecker didn’t even write a single quartet. Asshole.

Borodin’s tunes are so lovely that they famously made it to Broadway. He sure knew his chemistry, all right. No wonder he’s so beloved:

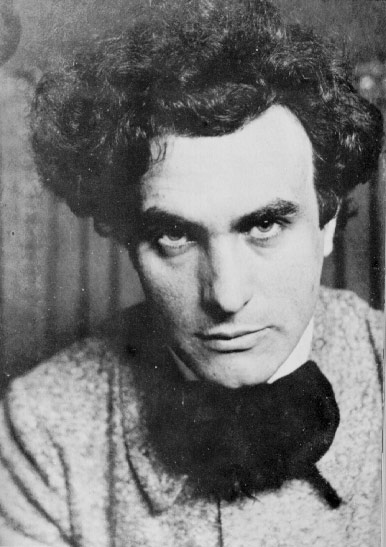

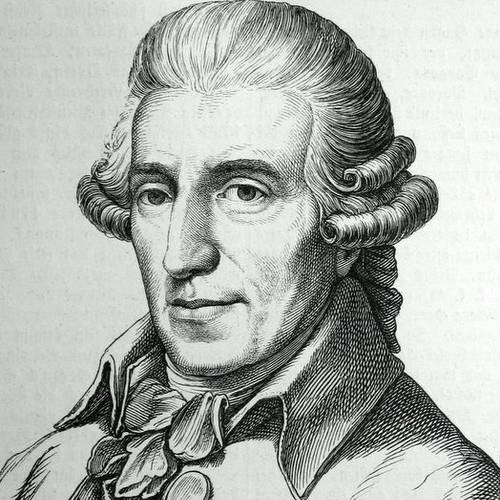

7. Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828)

Of the so-called “Vienna Four“, Schubert is the tuneliest. He may also be the ugliest, but we’ll save that discussion for a later list. Mozart tended to make his singers his instruments; Schubert made instrumentalists into singers.

Of the so-called “Vienna Four“, Schubert is the tuneliest. He may also be the ugliest, but we’ll save that discussion for a later list. Mozart tended to make his singers his instruments; Schubert made instrumentalists into singers.

Schubert also produced a stunning variety of melodies. The music of his late masses spins out into eternity, wrapping us in transcendence. A tune like “The Trout” is as solid and rustic as an Austrian lumberjack. But he could also write a gasping little noir melody like this one, which takes place entirely within one person’s soul:

8. Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901)

There is some very basic thing that doesn’t sit right with me about Verdi. But then I go to one of his operas, I do my best to inhabit his world of dramatic pacing, and the majesty and melodrama of his music win me over. Then I leave, and I sort of half-embrace him. And the cycle repeats itself.

There is some very basic thing that doesn’t sit right with me about Verdi. But then I go to one of his operas, I do my best to inhabit his world of dramatic pacing, and the majesty and melodrama of his music win me over. Then I leave, and I sort of half-embrace him. And the cycle repeats itself.

Was Verdi really a greater writer of melodies than his immediate predecessors, the bel cantists? That is really, REALLY hard to say, because they were all pretty damn good.

(La Traviata, Gheorghiu/Solti)

9. Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695)

I swear I’m not putting Purcell on here just to be weird or contrarian or whatever, but I will admit that I find his music incredibly unique, and that you’re very likely to see him on my “Personal Favorites” list. Part of the reason he’s getting on this list when all the other composers are 19th century or later is that he lived at this weird historical period when Tonal Harmony was not quite standardized, but it sort of worked, and I think this allowed him to use harmony in a way that I don’t hear from any other composer.

I swear I’m not putting Purcell on here just to be weird or contrarian or whatever, but I will admit that I find his music incredibly unique, and that you’re very likely to see him on my “Personal Favorites” list. Part of the reason he’s getting on this list when all the other composers are 19th century or later is that he lived at this weird historical period when Tonal Harmony was not quite standardized, but it sort of worked, and I think this allowed him to use harmony in a way that I don’t hear from any other composer.

I also think that he’s the only “classical” composer to write idiomatically for the English language, and he did it in a tuneful way that we wouldn’t see again until 20th century popular music came. Although that’s sort of complicated because a lot of his music sounds like what I’ve always guessed to be the pop music of his era.

(“If Music be the Food of Love”, King’s Consort)

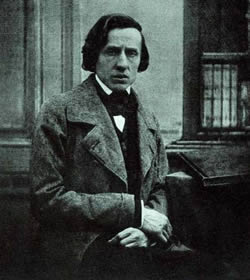

10. Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849)

Not being a classically trained pianist, Chopin will always remain something of a mystery to me. But again, he’s sort of like Verdi in my personal pantheon — I don’t think about him much, but when I’m listening to his music, I can’t resist its allure… until I start to get bored.

Part of the genius of Chopin’s melodic writing is that he took full advantage of his medium, the piano – when writing for the human voice, the range of a melody is much more restricted. I’m not easily won over by lots of fancy figuration — Chopin’s pianistic coluratura, if you will. But there are those times when Freddy gets out of his own way and presents his melodies in their gorgeous simplicity. I include him here because I think he had a wonderfully colorful harmonic palette, something that his great heroes of the bel canto often lacked.

(Eb Nocturne Op. 9, No. 2, Rubinstein)

Discuss

We’ve had some stirring commentary in the past few, so let’s keep it going. Tell your friends! I’ve already learned a ton from your collective knowledge.

In a lot of ways, this was my favorite list to make [because it sounds so preeetty]. I really hope we get some bel canto queens up in here talkin’ bout Gaetano Donizetti or some shit. And since we have no genre guidelines, I think this list more than any so far should bring up a lot of debate and new names.

Remember the rules of the game: either put up your own top 10 list; or, if you’d prefer to suggest an alternative to one of my composers, you must choose a composer to remove from my list. So let’s see how fast everyone can type “Purcell” and click submit.

Isn’t that kind of an embarrassing trove of ‘firsts’ for a man who’s been reviewing theater for like 20 years or something? Critic as fan v. critic as practitioner… I’d better stop before this whole thing turns into a post about Pauline Kael.]

Isn’t that kind of an embarrassing trove of ‘firsts’ for a man who’s been reviewing theater for like 20 years or something? Critic as fan v. critic as practitioner… I’d better stop before this whole thing turns into a post about Pauline Kael.]