Our fourth in the series of top 10 lists, this list focuses on people who might be termed “the best collaborative composers”. Composers who are distinguished by their contributions to film, theater, dance, TV, or some other non-musical medium. In some cases, their works have a life on the concert stage, or in yet another medium. In some cases, they also double as brilliant composers for the concert hall. (In other cases, they double as not-so-brilliant composers for the concert hall. Quite a smorgasbord we’ve got here.)

Each of these media requires something different. Opera, pantomime, and ballet often require the music to tell the story as much as the action on stage. Some music theater composers do this as well, but some just write great songs that propel their story along at a really entertaining clip. Movies, TV, and “incidental music” for the theater are different – if the music distracts from what’s going on in the drama, it has ceased to serve it’s function. But the really excellent composers for these media do more than just set a mood – they come up with ingenious ways of working the musical material into our minds and play subtle psychological games so that we interact with what’s going on in front of our eyes on a subconscious level.

1. Stephen Sondheim (1930 – )

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I think Sondheim is our greatest living American composer. The irony of my including him on this list, however, is that I always find that his music is ruined when I see it staged in the theater. His music (not to mention his lyrics) does such an amazing job of telling the story that I can lean back, close my eyes, and see every move, facial expression, and visual image in the play.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I think Sondheim is our greatest living American composer. The irony of my including him on this list, however, is that I always find that his music is ruined when I see it staged in the theater. His music (not to mention his lyrics) does such an amazing job of telling the story that I can lean back, close my eyes, and see every move, facial expression, and visual image in the play.

But it’s not Sondheim’s fault that the people in the business of recreating his works can’t possibly match his genius and live up to what he’s written. Here’s a glimpse of a nearly-original production of Sweeney Todd (the ’82 touring company). It’s directed by Hal Prince, so let’s just go ahead and call it “authentic”. Notice how Sondheim writes all of Mrs. Lovett’s slaps, stomps, and sighs into the music? That’s good theater.

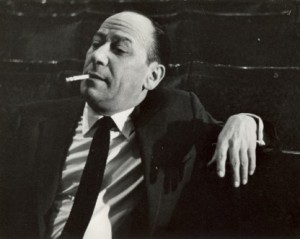

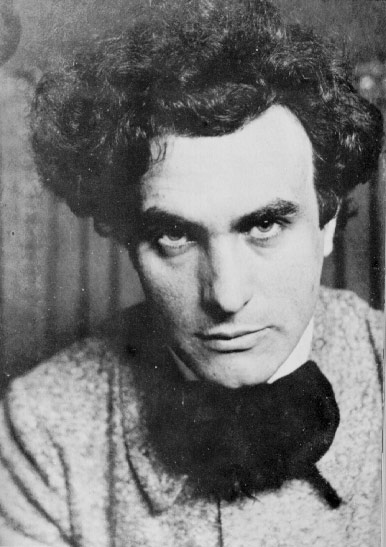

2. Bernard Herrmann (1911 – 1975)

Would Alfred Hitchcock’s films be what they were without Bernard Herrmann’s music? No way. His pre-Hermmann films were excellent, and had that certain Hitchcock touch, let there be no doubt: through Herrmann, we see Hitchcock at his best. Herrmann’s music elucidates and amplifies everything in Hitchock’s visual language.

He scored Orson Welle’s Citizen Kane. He scored Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. He wrote the iconic opening sequence for The Twilight Zone. What more do you people want?? Whatever it is, he’s got it. A horror score using only strings? Psycho. A heavily ironic score for a romantic comedy adventure? North by Northwest. An intricate psychological dreamscape? Try this:

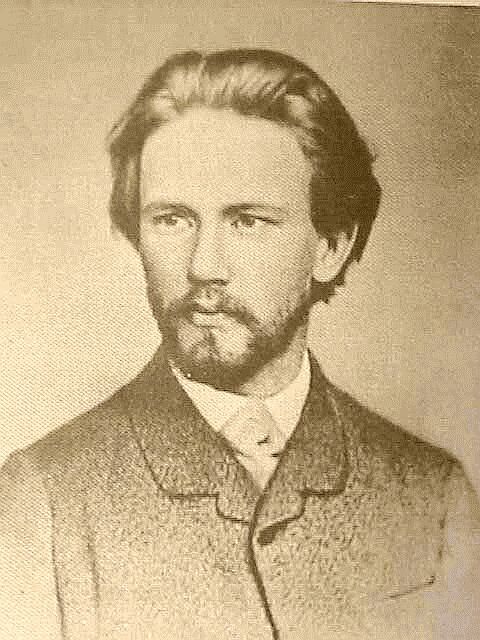

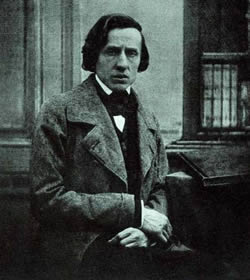

3. Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893)

Name a single ballet in the common repertory written before Tchaikovsky came along. The only ones I can think of are “Giselle” and… that’s it. Even Ballanchine said that before Stravinsky, the only ballet scores of any merit were Tchaikovsky’s. He is a brilliant musical storyteller. Add to that the fact that his music is so very danceable, and you’ve got a hit, baby.

More than any of the previous lists, this list is bound to reflect my personal view as an American. And what could be more American than seeing The Nutcracker during the month of December. No, seriously, I think we’re like the only country who really gets into this ballet at Christmas thing.

Swan Lake moves me to tears, and it’s no surprise that it’s featured prominently in films like Billy Elliot and the highly comedic and altogether craptastic Black Swan.

4. Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924)

Now, my friend Marcello and I have gotten into a lot of debates about Puccini v. Verdi. He thinks that Verdi is a better storyteller through music, whereas Puccini more or less writes soundtracks for the action on stage. Point well taken, though not entirely conferred.

My biggest problem with opera is pacing. A composer is invariably tempted to stop the action and tell us everything about a character’s inner depths. That’s great, and it’s a really unique property of music that it can do just that, so why not go for it? Because if the characters aren’t doing anything, why should we care about their inner lives?

For me, Puccini is that rare combination of an opera composer who can pace the action in a scene and simultaneously tell us everything we need to know about the characters in it.

5. John Williams (1932 – )

Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, Indiana Jones, E.T., Home Alone, Hook, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, Harry Potter, and don’t forget a little something called THE OLYMPIC GAMES.

Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, Indiana Jones, E.T., Home Alone, Hook, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, Harry Potter, and don’t forget a little something called THE OLYMPIC GAMES.

Yes, it does read like a Steven Spielberg filmography, but fine. The two are ideally suited for each other. They are both unabashed manipulators of our emotions, and they both do it incredibly well.

John Williams may be a red-handed thief when it comes to his material. But he doesn’t waste what he’s stolen. His music may be as cheezy as an overflowing fondue pot. But I bet all of you could sing the main themes from each of the above listed movies, and that’s saying a LOT.

I mean, come on, right?

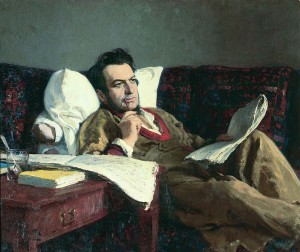

6. Leonard Bernstein (1918 – 1990)

Wait, so you’re saying street gangs don’t do ballet? Could have fooled me.

7. Alberto Iglesias (1955 – )

An analogy:

An analogy:

Iglesias:Almodóvar:

:Herrmann:Hitchcock

During their generation, Hitchcock and Herrmann were the most distinguished practitioners of their respective art forms. It also happens that they were ideally suited collaborators – they shared an artistic soul. One expressed that soul in a visual language, the other in an aural one.

I would say the exact same thing about Alberto Iglesias and Pedro Almodóvar. Again, the movies Almodóvar made pre-Iglesias are very much his own, and excellent in and of themselves. The ones he made with Iglesias as collaborator are just way better.

8. Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971)

Stravinsky’s first three major works, all ballets, are staggering accomplishments in every category: harmony, form, orchestration, instrumentation – everything. And I don’t care that we’ve lost a lot of the original choreography – I know that these are perfect works for the stage. Much like what I said about Sondheim, Stravinsky’s music tells the story.

My primary example would be Petrushka, his 1911 ballet about puppets coming to life (a Russian sort of Pinnocchio, you might say). Every character, every argument, every laugh is vividly portrayed in the music. Different musics interact with each other, and pile on top of each other, just like freaks at a carnival show.

He did plenty of experimenting in weird little stage genres, like pantomime (Renard), narrated chamber music (Histoire du soldat), and ballet chanté (Les noces). But what I find really striking is that he could be as moving in the overblown romanticism of The Firebird (1910) as he could be in the refined and formal classicism of Apollo (1928):

(and p.s. Herrmann:Hitchcock::Iglesias:Almodovar::Stravinsky:Balanchine, yes?)

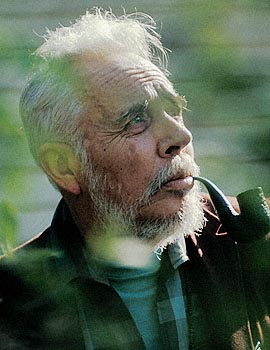

9. Frank Loesser (1910 – 1969)

I think Guys & Dolls is the perfect musical. Great tunes, great pacing, great dialogue – everything you’d want. The amazing thing is that Frank Loesser is the first and only Broadway triple threat, having written the score, the lyrics, and the libretto for this gem of the musical stage.

I think Guys & Dolls is the perfect musical. Great tunes, great pacing, great dialogue – everything you’d want. The amazing thing is that Frank Loesser is the first and only Broadway triple threat, having written the score, the lyrics, and the libretto for this gem of the musical stage.

Plus, how do you not include someone who looks like that?

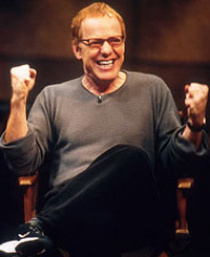

10. Danny Elfman (1953 – )

Everyone just looves to talk about how Danny Elfman doesn’t write his own music. Admittedly, there is so much rumor-mongering out there, it can be really hard to sort the facts from the fiction. I think this article makes a really good case, and I’m willing to take it at face value.

Everyone just looves to talk about how Danny Elfman doesn’t write his own music. Admittedly, there is so much rumor-mongering out there, it can be really hard to sort the facts from the fiction. I think this article makes a really good case, and I’m willing to take it at face value.

OK, so the guy writes his own music. And it’s really, really cool. I can hardly think of a more inventive score than Beetlejuice – it’s a wild romp, just like the movie itself. And who doesn’t tear up when that choir comes in at the end of Edward Scissorhands?

The pi̬ce de r̩sistance however, has to be Nightmare before Christmas РI loved it when I was a kid, and I was really surprised when I started conducting youth orchestras 10 years later that it was still so very popular.

(so, Danny Elfman:Tim Burton::… do we really have to go through this whole thing?)

Discuss

So that last list didn’t seem to generate much talk… I guess it was just a little too tame for the Webern crowd. But I’m anticipating that this list could get real territorial real quick. Will the opera queenz, the balletomanes, and the Hans Zimmer fanatics get all up in each others’ grillz? Will there by any video game music people out there? Will anyone say Adam Guettel? Will Gabe say Monteverdi?

And are there any Lost fans out there? I never watched the show, but I almost thought about including Michael Giacchino just on Alex Ross’s recommendation. And speaking of TV, how about Alf Clausen?

Just remember, we’re not trying to glorify any cults here; we’re just taking a chance to reason and discuss and think about music. But the fun of this game is to face the artificial limits it provides and organize your thoughts accordingly. So, either a) come up with and present your own list or b) suggest alternatives and remove someone from my list in so doing.

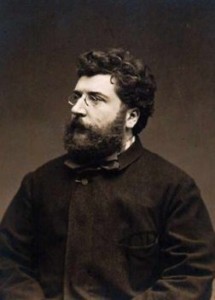

Not surprisingly, we come to another composer most well-known for his work in the theater. Carmen might be the greatest collection of tunes in opera. Note the distinction — not the greatest opera (though it sure ain’t shabby!), but the best set of tunes as an opera.

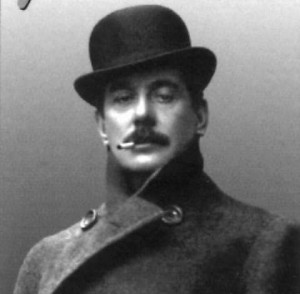

Not surprisingly, we come to another composer most well-known for his work in the theater. Carmen might be the greatest collection of tunes in opera. Note the distinction — not the greatest opera (though it sure ain’t shabby!), but the best set of tunes as an opera. The third Russian on our list, Mr. Borodin’s primary vocation was as a chemist (a rather dour chemist, from the look of it). For those who care about such things (or for those who just don’t have time to read the entire

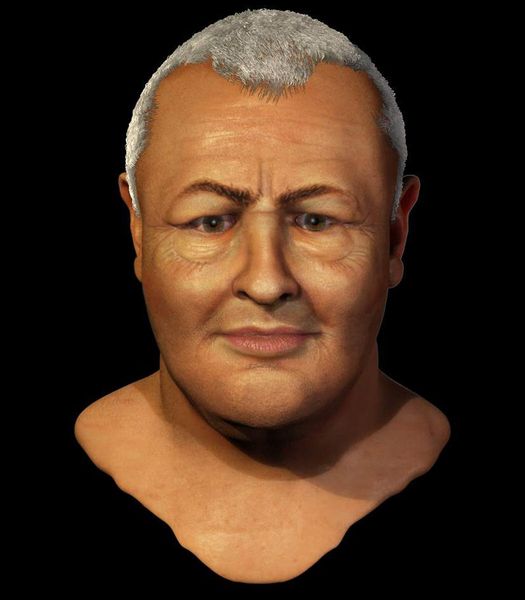

The third Russian on our list, Mr. Borodin’s primary vocation was as a chemist (a rather dour chemist, from the look of it). For those who care about such things (or for those who just don’t have time to read the entire  Of the so-called “

Of the so-called “ There is some very basic thing that doesn’t sit right with me about Verdi. But then I go to one of his operas, I do my best to inhabit his world of dramatic pacing, and the majesty and melodrama of his music win me over. Then I leave, and I sort of half-embrace him. And the cycle repeats itself.

There is some very basic thing that doesn’t sit right with me about Verdi. But then I go to one of his operas, I do my best to inhabit his world of dramatic pacing, and the majesty and melodrama of his music win me over. Then I leave, and I sort of half-embrace him. And the cycle repeats itself. I swear I’m not putting Purcell on here just to be weird or contrarian or whatever, but I will admit that I find his music incredibly unique, and that you’re very likely to see him on my “Personal Favorites” list. Part of the reason he’s getting on this list when all the other composers are 19th century or later is that he lived at this weird historical period when Tonal Harmony was not quite standardized, but it sort of worked, and I think this allowed him to use harmony in a way that I don’t hear from any other composer.

I swear I’m not putting Purcell on here just to be weird or contrarian or whatever, but I will admit that I find his music incredibly unique, and that you’re very likely to see him on my “Personal Favorites” list. Part of the reason he’s getting on this list when all the other composers are 19th century or later is that he lived at this weird historical period when Tonal Harmony was not quite standardized, but it sort of worked, and I think this allowed him to use harmony in a way that I don’t hear from any other composer.

Isn’t that kind of an embarrassing trove of ‘firsts’ for a man who’s been reviewing theater for like 20 years or something? Critic as fan v. critic as practitioner… I’d better stop before this whole thing turns into a post about Pauline Kael.]

Isn’t that kind of an embarrassing trove of ‘firsts’ for a man who’s been reviewing theater for like 20 years or something? Critic as fan v. critic as practitioner… I’d better stop before this whole thing turns into a post about Pauline Kael.]